Q:

You’ve been in leadership positions, and you’ve

watched leaders for a long time — what do you think

are the greatest strengths in public sector leadership

today? What are their greatest weaknesses?

If I think about healthcare, there are many people itching to

make changes for the betterment of patient care. For decades we

have talked about the social determinants of health. Improving

income is key. What is an individual doc to do with that? Well,

at St. Mike’s in Toronto there is a real attempt to make sure their

patients are getting all their income benefits. And Dr. Ryan Meili

and colleagues in Saskatoon have a program called UPSTREAM

which actually clothes principles in reality. The re-discovery of

the Guaranteed Annual income and the substantial policy work

on the topic forty years ago has engaged public servants (in On-

tario, at least) and the social organizations outside government

looking for better ways to direct income to poor people. This so-

cial engagement and blurring of policy lines takes real leadership

and I see it as very positive.

Q:

Those examples are rare, though.

They are. The last several decades and have been very difficult for

anyone who is inspired by a desire to see a fairer society. The pen-

dulum swing following the 1978 Bonn summit was the beginning.

Frankly it has been hard for the ordinary person to see themselves

in government policy since. Maybe that is why Trump and Sand-

ers have been having such a run in the US primaries. Even now

in Canada we do not talk about poverty. We talk about the middle

class. I recently did a bit of research for a conference on basic in-

come and it is sad to see how little progress has been made. The

Ken Carter Commission on Taxation concluded (in 1966!) that the

tax system placed an unfair burden on the poor. The Senate Com-

mission on Poverty of 1971 concluded that Canada should adopt

a guaranteed annual income. Almost 50 years later, we’re talking

about it like it’s a new idea! The Royal Commission on the Status

of Women and, in the early 80s, the McDonald Commission on the

Economy all came to the same conclusions. I was lucky to have

begun a public service career when the fashion was public and so-

cial engagement. Searching for evidence was expected, as was en-

gaging in discussion and, if necessary, argument with your Deputy

Minister or Minister (as long as you were polite and respectful). I

really don’t know now. It seems to me that in Ottawa, and in most

provincial capitals, those reflexes might be a little rusty.

Q:

So what keeps you optimistic and engaged?

I really do believe a better world is possible. I also believe that it

requires relentless effort to change anything. At CFHI, with our

small budget ($17 million in the face of a $220 billion healthcare

spend in Canada), we can make a difference and most importantly

we are already showing that good ideas applied, tested and evalu-

ated can be spread by willing imitators and adapters. Patient care

will improve and it will likely cost less than now. Change always

14

/ Canadian Government Executive

// June 2016

The Interview

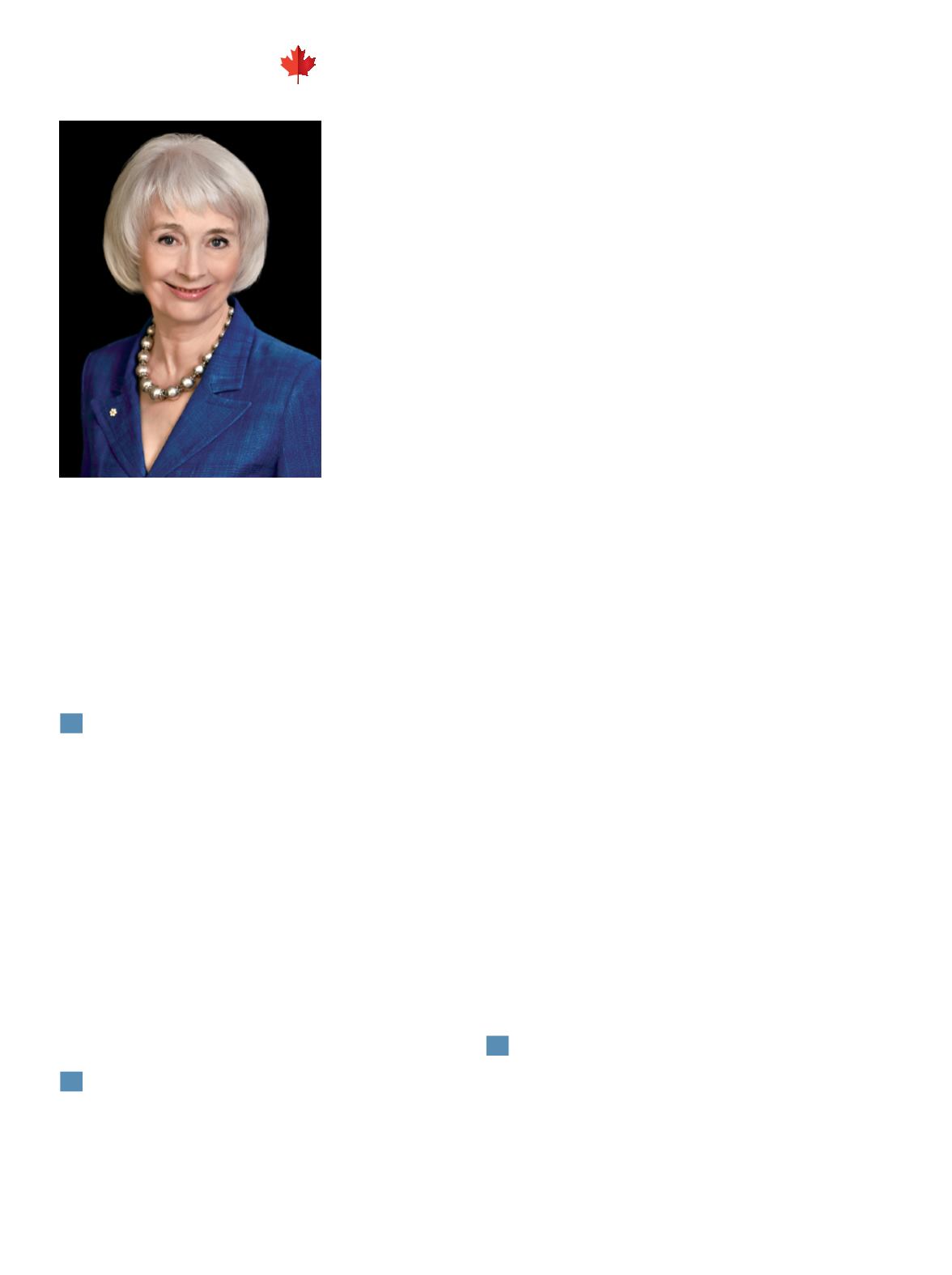

Maureen

O’Neil

Maureen O’Neil

has been leading the CFHI since 2008, but she’s been fighting battles in the policy

trenches with her signature energy and enthusiasm for decades. She has served as President of the

International Development Research Centre, Interim President of the International Centre for Human

Rights and Democratic Development, President of the North-South Institute, and Deputy Minister of

Citizenship, Government of Ontario. She serves on a broad range of boards at the provincial, national

and international levels. Patrice Dutil, the editor of CGE, caught up with Ms. O’Neil to talk about lead-

ership in creating a culture of sustained innovation.

On Leadership, Healthcare,

and Innovationwith

President of the Canadian Foundation

for Healthcare Improvement