10

/ Canadian Government Executive

// October 2016

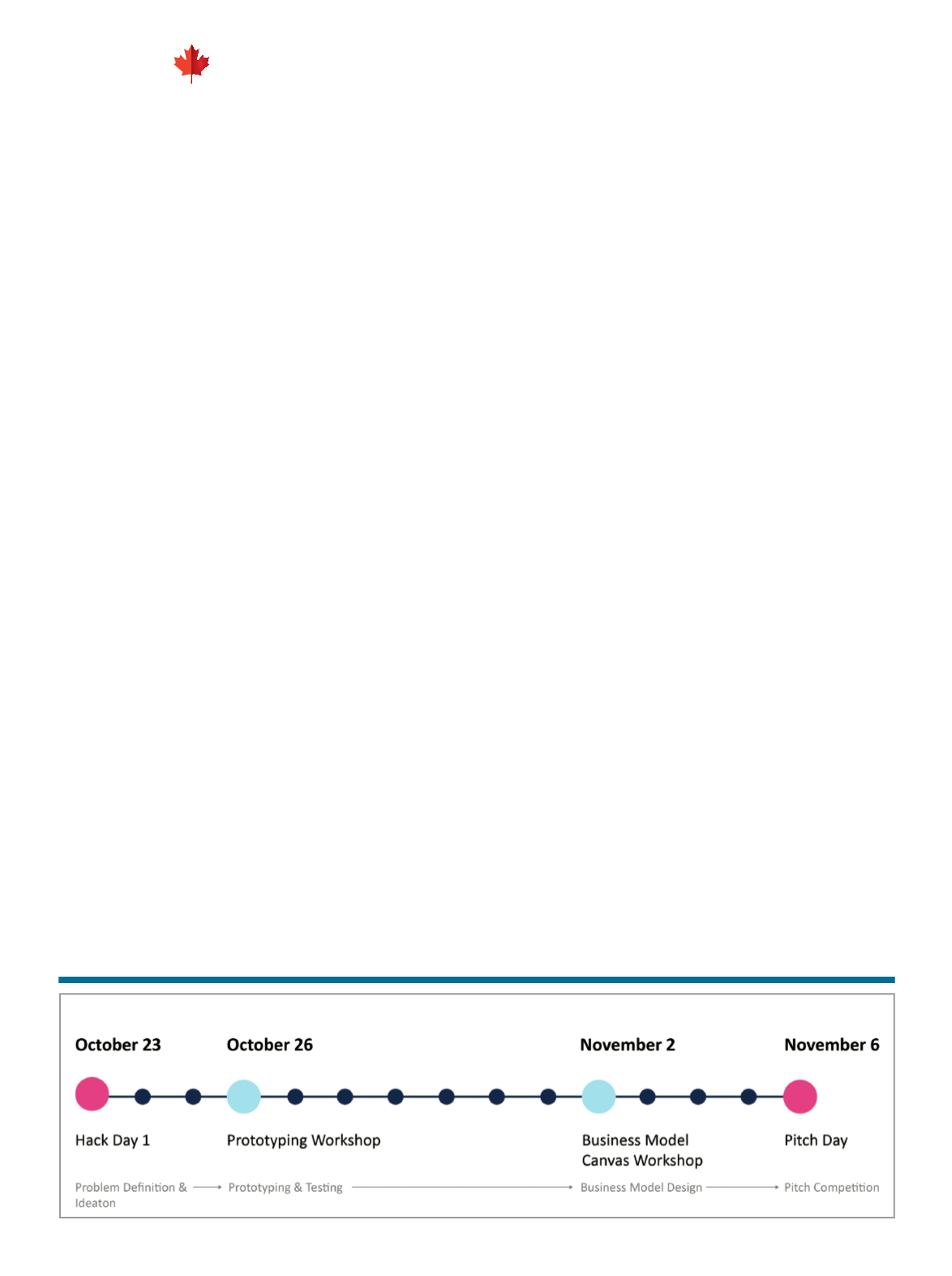

Figure 1.

Timeline for Hack

Kelly McShane,

Leanne Wilkins,

Andrew Do,

Annalise Huynh

and (3) advocacy on behalf of innovation

and entrepreneurship across the country.

In June 2015, the Ontario Public Service

(OPS) approached the BII+E to explore

how its abilities could be applied to policy

challenges. A first step was the creation

of the Policy Innovation Platform (PIP), a

pilot initiative to assist policy profession-

als in generating innovative solutions to

complex public policy problems. The OPS

provided support via the secondment

of a policy director and an agreement to

provide challenge issues that would be

tackled via the Platform. The PIP would

be a neutral space for policy profession-

als to test new tools and methodologies

for developing policy, including design

thinking: using data analytics, rapid pr-

ototyping and crowdsourcing.

The first “challenge issue” presented to

the Brookfield Institute and the PIP was

this: how to improve the implementation

of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Dis-

abilities Act (AODA)? Although the AODA

was legislated in 2005, a number of imple-

mentation challenges remained in its quest

for to achieve a baseline of accessibility

in Ontario by 2025. The issue was refined

with the Accessibility Directorate of Ontar-

io as “How can we accelerate the dialogue

on accessibility with the goal of helping to

shift attitudes and change behaviour?”

To answer this question, the PIP orga-

nized a Hack, taking the unique title of

“Hack-cessibility.” “Hacking”—a term bor-

rowed from the world of computer science

to designate outsiders who would creative-

ly to crack codes designed to protect insti-

tutions, typically with malicious intent.

In our case, the motivation was hardly

T

here is already a surging litera-

ture on the application of design

thinking (DT) to government

services. Ressler and others

have argued that DT pays dividends to

many: to citizens, who benefit from more

sharply focused programs and to elected

governments as well, who may benefit

from more satisfied voters. In many juris-

dictions, the main institutional vehicle to

bring in DT has been the creation of in-

novation labs, many of which have been

described in this magazine by Patrice Du-

til and Peter Jones. Still, the spread of DT

across government is far from complete.

Many argue that design thinking should

be at the forefront of any attempts to

bring changes to both policy and program

implementation.

There are many ways to trigger DT. In

this article, we present the application of a

“hack” to address a policy question posed

by the provincial government of Ontario.

It was organized by the Brookfield Insti-

tute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship

(BII+E), a new, independent and non-

partisan institute housed within Ryerson

University, that is dedicated to help make

Canada the best country in the world in

which to be an innovator or an entrepre-

neur. It supports this mission in three

ways: (1) insightful research and analysis;

(2) testing, piloting and prototyping proj-

ects; which informs BII+E’s leadership

malevolent, but it did retain the mission

of “cracking” obstacles such as received

attitudes, outdated processes and weak

policy partnerships. The intention was to

push participants not only to think about

policy but to craft tools that could actually

be used quickly to accelerate the dialogue,

shift attitudes and change behaviour.

The Hack-cessibility brought together

policy professionals, community leaders,

policy experts, people facing accessibility

issues and students. They were grouped

in multidisciplinary groups of four to six

people. The Hack was executed over the

course of two weeks and four events (see

Figure 1). Throughout the Hack, teams re-

fined, tested, and strengthened their ideas

through a facilitated process.

That process included a series of se-

quenced activities that were intended to

guide participants through different stag-

es of problem-solving inspired by human-

centred design. These stages included

problem definition, ideation, prototyping

and testing, business model design, and

pitches. For the challenge of shifting the

dialogue on accessibility, it was crucial to

centre the process on the perspective of

user groups with lived experience of ac-

cessibility challenges. There was a need

to lead the process design—and to scope

useful and innovative solutions—without

co-opting this lived experience or under-

mining existing work.

The process design was co-created by the

evaluation users and an external consul-

tant. It carried the objectives of (1) support-

ing facilitators in guiding teams through

the design thinking phases; (2) setting

participants up for success in designing

Design

The “Hackathon” As an

Instrument in Policy Design