10

/ Canadian Government Executive

// November 2016

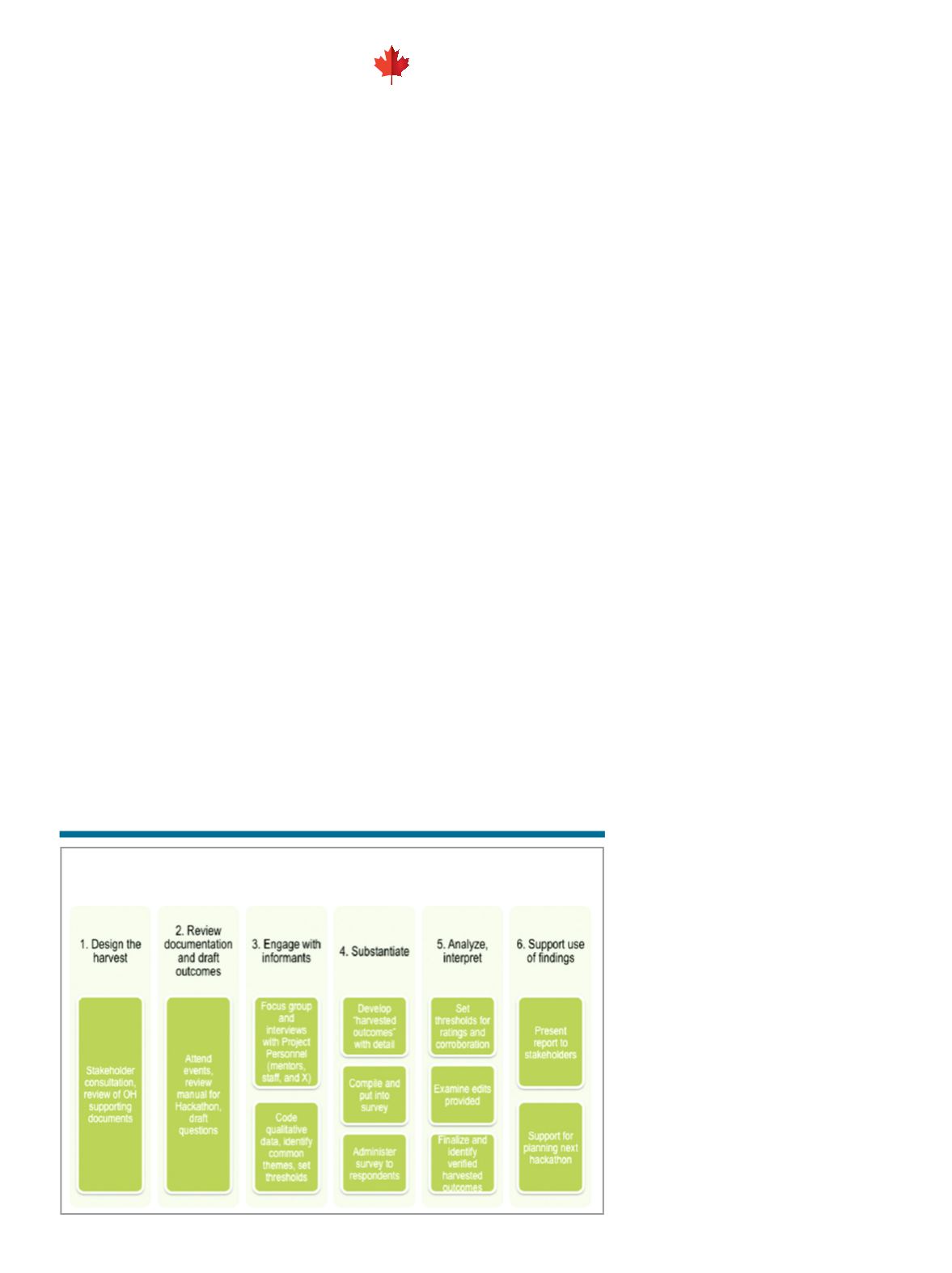

Figure 1.

Overview of Outcome Harvesting based on Wilson-Grau

and Britt (2012)

Kelly McShane,

Leanne Wilkins,

Andrew Do,

Annalise Huynh

key task of the evaluator is to draw and

verity the connection between the pro-

gram and the outcome. What makes this

“detective work” original is that the iden-

tification and verification of outcomes oc-

curs after the program has occurred and

after the change has occurred. The steps

in outcome harvesting are presented in

Figure 1, alongside the details specific

to the current project in order to ground

our example in the theoretical framework

provided by R. Wilson-Grau and H. Britt

in their work

Outcome harvesting

(Ford

Foundation, 2012).

The Brookfield Institute

for Innovation + Entrepre-

neurship Case Study

We applied OH to a “Hackathon” pilot

project. A Hackathon is generally defined

as a set of events where individuals come

together to solve a problem in a creative

manner. The event is typically run by facili-

tators and can include content experts (in

our event, they were named mentors). The

process is fluid and the solution is unknown;

both of which make the task of evaluating

outcomes incredibly challenging.

In such a dynamic and uncertain envi-

ronment, OH is appropriate because the

objectives and change pathways are not

fully articulated given the complexity of

programming.

O

ne of the most difficult aspects

of program evaluation is dem-

onstrating its outcomes. The

challenge is persistent: can the

“new reality” of a person who has experi-

enced a particular program be attributed

to the program itself or is there another

variable than can explain the change?

Outcome Harvesting (OH) is a new

method that allows evaluators and stake-

holders to make sense of outcomes at the

conclusion of a program. Specifically, it

involves the identification, formulation,

analysis, and interpretation of outcomes

to answer questions that are particularly

relevant to stakeholders. Outcomes are

considered in their broadest sense, span-

ning changes in behaviours and actions,

relationships, activities and practises, and

policies. These outcomes can belong to

individuals, groups and communities, and

organizations and institutions.

In OH, the evaluator takes on the role of

a detective by combing through reports,

interviews, and other sources in their

quest to capture how a given program or

project has brought about outcomes. The

We also elected to use OH because of

the developmental nature of the evalua-

tion. Specifically, the evaluation user (cli-

ent), Brookfield Institute for Innovation +

Entrepreneurship (BII+E) was embarking

on its first of numerous hackathons and

the opportunity to learn in “near real time”

on the change processes would better po-

sition future hackathons. Thus, for these

two reasons, the complexity and opportu-

nity for learning, outcome harvesting was

selected as the methodology.

How it works: Setting up

the “Harvest”

In the first iterative step, the evaluation

team (McShane and Wilkins) met with the

evaluation users (Do and Huynh) to deter-

mine the scope of the outcomes, individuals

and organizations tied to the hack, as well as

their initial ideas on how changes might oc-

cur. This allowed for the creation of a set of

open-ended questions (second step).

Questions were purposely broad as ini-

tial conversations indicated that a range of

possible outcomes that covered personal

and organizational. The users were inter-

ested in knowledge and change related to

accessibility and the interest and applica-

tion of design thinking in a policy context.

A series of interviews and focus groups

were conducted (step 3) with 4 members

from the users’ core team (100% of mem-

bers), 4 mentors (33% of mentors) and

11 facilitators (69% of facilitators). The

evaluation team compiled responses and

organized them in a grid fashion, noting

Change, Who, When, How for all out-

comes. Decisions were made regarding cri-

teria to be met in order to make the short-

list of outcomes to later be substantiated.

For example, we decided that two differ-

ent respondent groups needed to suggest

the change in order for it to be added to

the list of outcomes to be substantiated. At

times, the same outcome was mentioned,

but the explanation for how was differ-

ent. In such instances, the team worked to

unify and develop a more comprehensive

explanation for the change to bring for the

to the substantiation phase.

What did the “Harvest”

Yield?

We identified of six outcomes (in three do-

mains) through this process (see Table 1).

Program Evaluation

Outcome Harvesting to

Evaluate Social Innovation