20

/ Canadian Government Executive

// April 2016

Middle Management

John Wilkins

public servants but only 1% of EXs, are being accelerated into the

middle management gaps emerging. The EX pool is also diversi-

fying, with 46.1% women, 3.7% aboriginal, 5.4% disabled, and 8.5%

visual minorities.

Cohort value systems and aspirations are vastly different and

require different management responses.

Reshaping the middle

The new governance paradigm is collaborative, connected, inter-

active, and engaging. The challenge is to span boundaries between

regions, countries, jurisdictions, and sectors and to integrate is-

sues across institutional, policy, and management capacities. Like

star gazing, leadership is about looking up, seeing the big picture,

and connecting the dots of the puzzle.

Middle managers no longer operate in a world where being

in the middle means having cut-and-dried responsibilities. They

thrive on networking across boundaries, connecting the dots, and

responding to crises with integrated expertise and savvy. Progres-

sive public institutions reshape the middle as a place where man-

agers learn collaboratively.

Middle managers need to be incentivized to ask new questions.

For example, simulations help them envision daily problems differ-

ently in order to cope in a complex, turbulent, and demanding en-

vironment. They imagine new situations in ways that stretch think-

ing beyond raw tasks and efficiency. Asking new questions prepares

middle managers to learn and innovate, not just to execute.

The next generation of public managers is poised to assume the

helm of virtual organizations that are built of energy and ideas.

Valuing learning competencies offers renewed impetus for di-

versity of thought and innovation. There is nothing conventional

about managing in the middle.

J

ohn

W

ilkins

is Associate Director, Public Management with

the Schulich School of Business, York University (jwilkins@

schulich.yorku.ca). He was a career public service manager in

Canada and a Commonwealth Diplomat.

W

ith the naked eye, we connect star points and vi-

sualize constellations as mythological characters.

With scientific knowledge and instruments, we

study planets, solar systems, galaxies, and cosmic

phenomena. The mysteries of the universe are more deeply stir-

ring to our blood than any imagining.

The human condition echoes the infinite variety of the universe.

Diversity traditionally focuses on equity and fairness for legally

protected populations. It is measured along countless dimensions —

race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, age, physicality, religion, pol-

itics, ideology. Each person has individual differences and is unique.

The challenge is to harness a more powerful, nuanced diversity

by untangling how people think and solve problems. According to

Deloitte, diversity of thought can help guard against groupthink

and expert overconfidence, increase the scale of new insights, and

identify the right people to tackle the most pressing problems.

Multi-tasking and technological advances trigger creative problem

solving, careful decision making, and successful implementation.

Rethinking the role of diversity of thought in change manage-

ment has never been more opportune. Governments need to spon-

sor different thinking styles to retain and advance cognitively

diverse talent. They need to diversify competencies, recruit top

prospects, and cultivate opinionated people to shake up the status

quo. Managers should encourage task-focused conflict to push cre-

ativity and productivity. Team-based performance management

can foster an inclusive, empowering culture of innovation.

Leading across generations

The generational changeover confronting the public service

embodies the diversity challenge. Baby Boomers have dominated

for three decades and are checking out in record numbers. In the

Public Service of Canada, 16.3% of public servants are projected to

retire over the next five years. The impact is being felt in an older

Executive cadre, where 53.7% are Boomers, half with 30-years-plus

of service.

Leadership is falling to the Generation X feeder group, which is

45.3% of EXs. Inexperienced New Millennials, representing 21% of

The Millennials in Middle Management

“Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet.”

— STEPHEN HAWKING

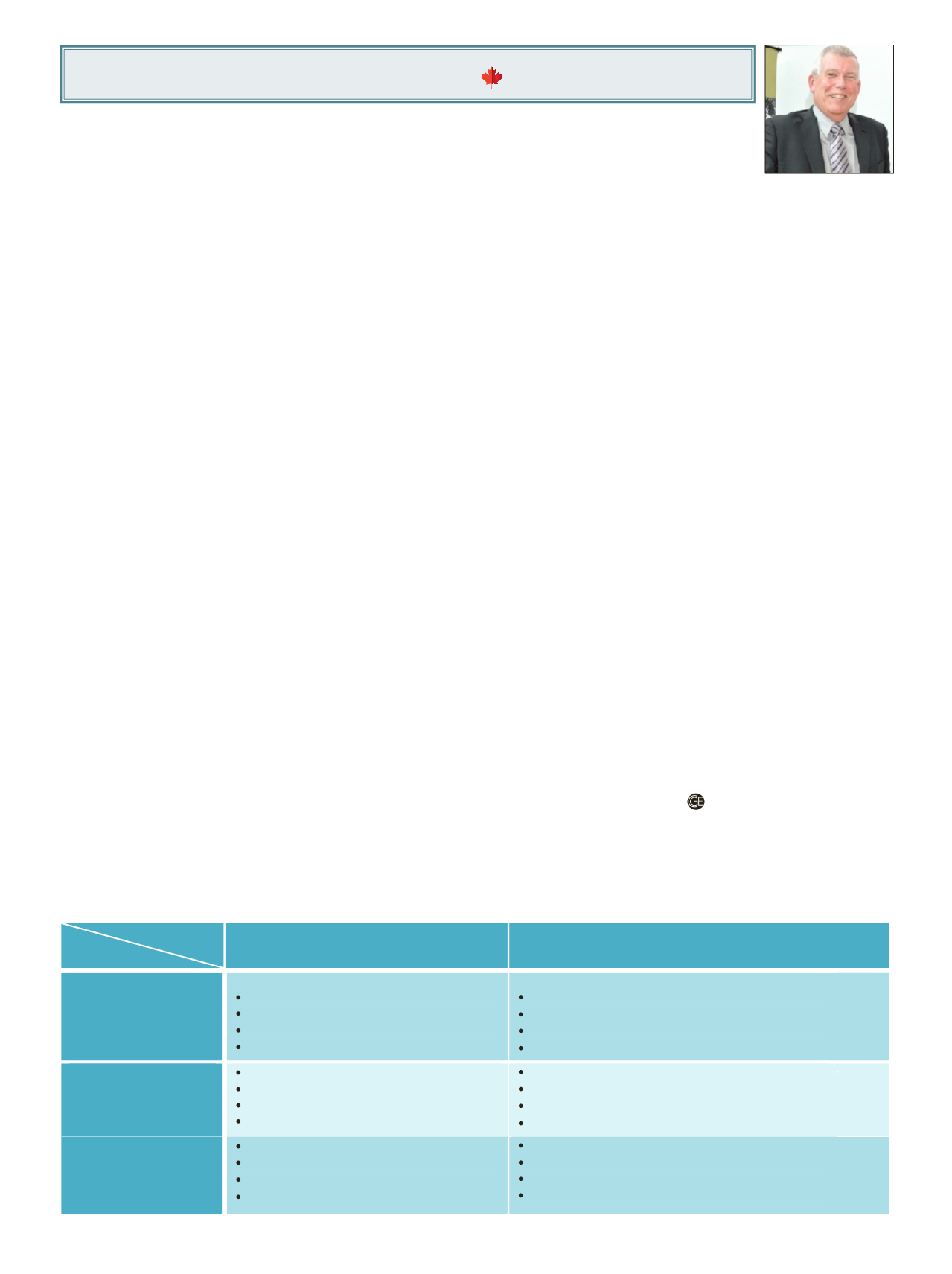

RESPONSES

COHORTS

DOs

DON’Ts

BABY BOOMERS

1946-1964

Spend Ɵme geƫng to know each other

Invite their insights as workforce veterans

Update them regularly on progress and changes

Embrace ways

they

can

contribute and benefit

Don’t overlook conversaƟon and the human touch

Don’t overuse technology for follow-up

Don’t forget to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ and mean it

Don’t ignore asking for their help or advice to earn trust

GENERATION Xers

1965-1979

Enable flexibility and freedom

Communicate expected results directly to them

Encourage working smarter, not harder

Promote portable self-development

Don’t focus on working hours and Ɵme pressures

Don’t expect them to trust management or poliƟcs

Don’t dwell on long-term vision and strategy

Don’t micro-manage vs. delegaƟng and supporƟng

NEW MILLENNIALS

1980-2002

Clarify structure, roles, and expectaƟons

Communicate task-specific moƟvaƟon

Incorporate peer mentoring and feedback

Invite their ideas while remaining supporƟve

Don’t expect sequenƟal order instead of mulƟ-tasking

Don’t lecture or philosophize on issues at hand

Don’t dismiss social media over formal communicaƟons

Don’t micro-manage vs. learning by doing and debriefing