22

/ Canadian Government Executive

// October 2016

Middle Management

John Wilkins

an invention of the international ‘best practices’ consulting crowd.

Some say that accountability is a construct so alien to human

nature that certain cultures have no counterpart word or phrase

in their language. Pacific Islanders, for example, choose fealty to

a village chief as good governance. In the Samoan public service,

few challenge incumbent CEOs for their jobs when up for renewal

out of respect for a chief or elder.

It is also important to understand what accountability is not.

The secret to accountability is to put the burden of proof on unac-

countability – innocent until proven guilty, trust before mistrust,

outcomes over compliance. Author Scott Turow opined, “The pros-

ecutor, who is supposed to carry the burden of proof, really is the

author.” In other words, the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

The quest for proof

Government carries the burden of intense pressure to make better

choices, deliver results, and demonstrate accountability. Middle

managers struggle to exercise strategic foresight in complex times.

Some eschew evidence-based approaches to policy and programs.

Others know that strategic foresight leans on historical evidence

to shape plausible, emerging futures.

Governments have been collecting and generating vast amounts

of data for decades. Data ownership and infrastructure silos im-

pede information sharing and stewardship. Analytics can help

produce better services that cost less and deliver more while pro-

tecting Big Data as a strategic asset.

Practice sometimes confounds theory in public management.

Evidence breathes experience, insight, and analysis into policy

gaps. Academics, think-tanks, and consultants glorify the evidence

with their expertise, but none are entirely free of bias. The whole

story gets told when perspectives are shared.

When research is farmed out, advice can fall beneath our wis-

dom like a stone. The lament is: “They do not really appreciate

the issues facing government.” Middle managers, who thrive on

deciphering the prevailing ambiguity, are called upon for their in-

tuition and judgement to make things work.

Producing evidence is a fragile process that is essential to good

governance. The challenge is to manage a rational, evidentiary

process against the odds. The trend toward policy-based evidence

rather than evidence-based policy offers scant comfort to politi-

cians when held to account.

Canada is comparatively proficient in understanding and imple-

menting accountability frameworks in government. However,

public institutions may be relying too much upon central over-

sight bodies to monitor performance instead of measuring the

outcomes of design and delivery themselves.

The call for innovation returns inevitably to the virtues of let

the managers manage. Accountability, in balance with autonomy,

can leverage central agency support for change. Advocates of the

results agenda are usually less convinced by arguments for inno-

vation than by the prospects of greater control.

J

ohn

W

ilkins

is Executive in Residence: Public Management

at York University.

jwilkins@schulich.yorku.ca.He was a

career public servant and diplomat.

W

hen public administration students insist upon a

working definition of accountability, textbooks rare-

ly satisfy. They are puzzled when accountability is

equated with responsibility, liability, or answerabil-

ity. Whatever interpretation is assumed gets probed and debated

for the rest of the course. The burden of proof is on the professor

and is intrinsic to grasping the meaning.

In business, employees are responsible for the results of assign-

ments performed and for accepting the consequences of their ac-

tions. Public servants know instinctively from experience that ac-

countability is much more. Their obligation is to report evidence

of results achieved in return for the responsibility, authority, re-

sources, and trust conferred.

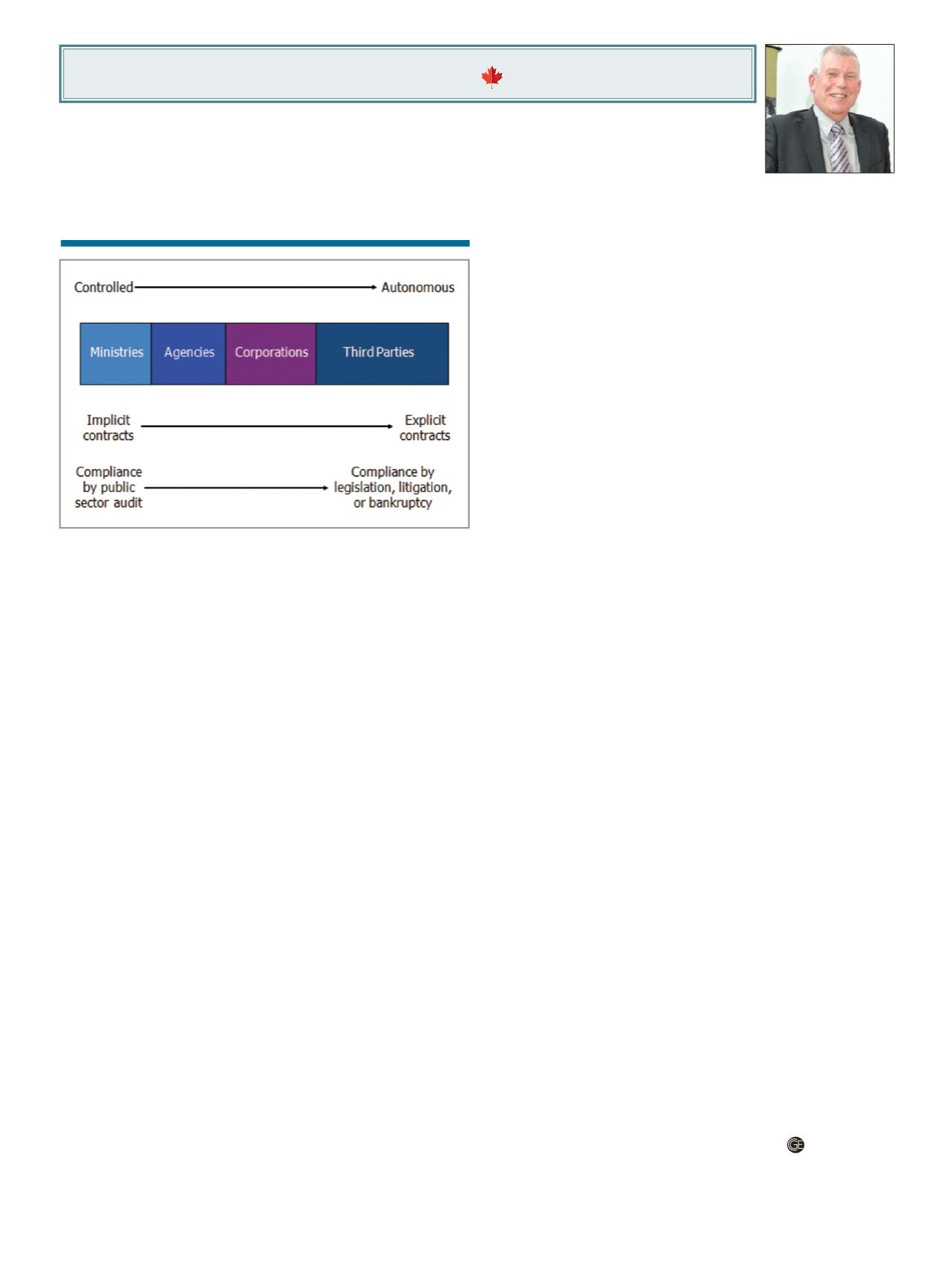

Accountability is institutional, as well as individual. The chart

above depicts the range of institutional governance, where auton-

omy increases from left to right. Accountability standards remain

constant across the spectrum, but the means vary with indepen-

dence. The rule of thumb is that ministerial departments are sub-

ject to oversight regimes that span government, whereas arm’s-

length bodies rely upon governance internal to the institution.

Modern notions of accountability favour results over process,

continuous learning and improvement, and dynamic responses to

complex uncertainties. Three principles underpin good practice:

1.

Responsibility – trusting and staying true to mandate in deci-

sions;

2. Responsiveness – addressing the need or rationale for the pro-

gram; and

3. Competency – doing the best possible job, given the circum-

stances, resources, and constraints.

The accountability challenge

Accountability is like Buckley’s Cough Syrup – it tastes awful, but

it’s good for what ails you. It is a decidedly Western ideal, born of

scientific and bureaucratic management traditions. Its conjoined

twin is Transparency. Together, they anchor public service per-

formance under the rubric of Results Based Management, itself

The Burden of Proof: Accountability

“The secret to happiness is to put the burden of proof on unhappiness.”

— Robert Brault