“Local government touches all of us intimately every day of our lives: the water we drink, the transit system that takes us to work, the first responders who keep our cities safe. Those services are only as good as the people who deliver them, and the quality of the people at the working level is determined by the quality of the leadership they receive,” concludes David Siegel in his excellent review of municipal leadership in Canada, Leaders in the Shadows. The focus of the book is on the municipal Chief Administrative Officer, but its lessons in leadership apply throughout the public sector.

This book is a rich source of insight about leadership in government. It explores what leadership is and the ideas over time that have shaped our thinking about it. Siegal gives us five case studies of CAOs who have had an impact on their communities they have served. From those cases and that theory, he draws important lessons about leadership in government. They apply well beyond the municipal sector.

There are many characteristics of municipal government that make it unique and challenging. That can be said of any part of the public sector. Municipal governments have a high degree of transparency. Advice is seldom provided in confidence. There is a complex mesh of stakeholders. It is highly service oriented. The CAO also serves many masters, being appointed by the Council and working within its decision-making framework, which is quite different from the Westminster model. The election cycle is set and relatively short. The responsibilities of the CAO are diverse. That person can never be master of them all so must build a team of experts and create a unifying strategy for them.

CAOs are expected to not lead the political masters, but serve them with advice, expertise and implementation. As Siegel says, “In municipal administration, things that work well are invisible.” And, central to his theme, they lead in the shadows, ensuring that those above provide the democratic leadership they are elected to do, those to the side – the stakeholders and partners – have their interests addressed and those below bring their expertise and action capacity to the game.

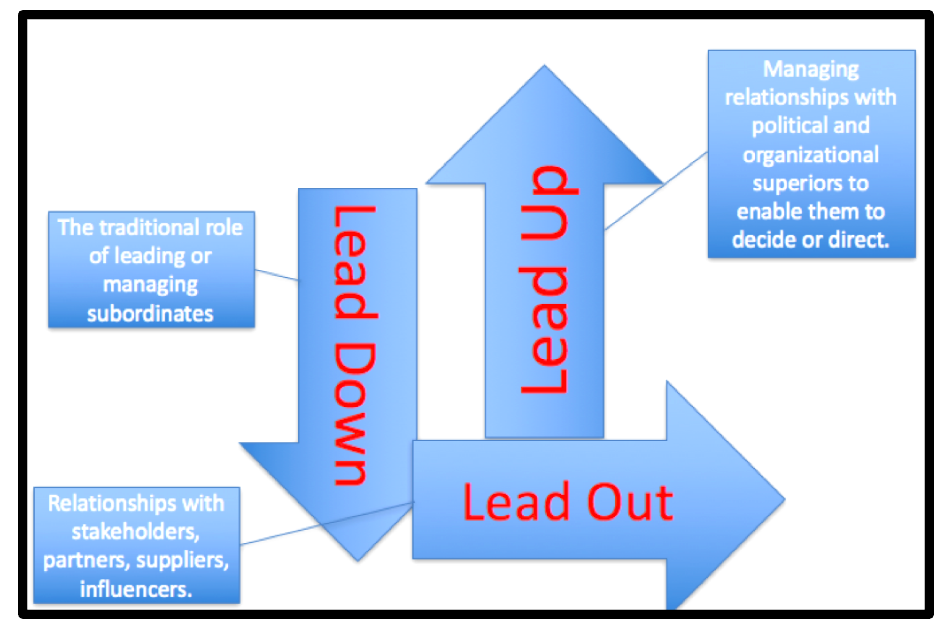

Siegel’s model of up, down and out leadership resonates with how public sector leadership has to be practised to be effective. One element of this leadership that the literature does not do a good job of describing is understanding that the upward leadership is such a unique feature of the public sector leadership. Catherine Aulthaus of Australia and New Zealand School of Government has called this the Administrative Sherpa role of leadership, in which the public servant, through expertise, analysis and advice, leads decision-makers towards their public policy decision, providing the best evidence for them to choose their course of action. Here is how I have tried to interpret Professor Siegel’s model graphically:

Reading the case studies is highly instructive. All the individuals have practised their leadership in municipal government, some large, some small. Siegel documents each journey and draws lessons from each. All these cases show us a leader leading a multidisciplinary or multi-business organization. This is often the case in government. Some of the lessons reinforce findings that we have seen elsewhere. Siegel just makes them more real and grounded.

Some of the lessons learned from these cases and Siegel’s analysis are:

- “Great Man” and “Command and Control” are unworkable notions of leadership in this context – and in most of government.

- There is a place for command and control but that is not leadership.

- Leadership is about building motivation and building agreement on action.

- There is a variety of ways to get things done as long as you know have clarity on the problem to be solved and the goal to be reached.

- Leaders orchestrate expertise. They do not replace it.

- The degree of influence and trust is a key metric of leadership.

- A leader works with many people, with different interests and views.

- A public service leader is not a political actor, but must act with political sensitivity.

- Leaders monitor performance but do not micromanage it.

- The many aspects of culture are a preoccupation of a leader. For a public sector leader, this involves many cultures, not just the bureaucratic one.

- Leaders leading in three different directions will vary the intensity of their focus based on their assessment of where they are needed, where the greatest risks are and the urgency of the issue.

- A public sector leader leads upwards as a trusted professional, not as a political actor. Building trust – upwards, downwards and sideways – is key to being successful.

Siegel says “I intended this book to contribute to the literature by identifying the specific traits, skills and behaviours found in senior municipal managers in Canada and to serve as a roadmap for mid-career public servants who aspire to become senior managers.” He has done this and more. He has documented for all to read the complex and demanding world of municipal public administration. But, for any government executive, he has given some models to emulate and some real insights into the world of public sector leadership.