The federal government has dramatically increased the scope and scale of its consultations and engagement in the past two years. The goal is to make it easier for public servants, citizens and stakeholders to work together to solve common problems and improve outcomes.

My team at the Privy Council Office monitors the success and impact of these efforts. We continually strive to learn, improve, and address barriers to good engagement. We track the progress of engagement so we can report meaningfully on the results, and share what we learn with others.

Why does it matter? Good engagement in the context of developing public policy is a way to regain public trust. But how? In theory, broadening the types of evidence considered improves the likelihood that the resulting program, policy or service will reflect the needs of the people it serves. The relationships needed to implement policies can form during these times.

What keeps me up at night is that bad engagement does the exact opposite of good engagement. Insincere engagement breaks relationships and erodes trust. It increases polarization and isolation, which can lead to extreme behavior. It can also reduce buy-in when it comes time to implement. Engagement done poorly further separates people in various sectors and ultimately undermines the goal of achieving shared societal outcomes.

In opening up our engagement processes to more people, we have seen both good and bad examples of engagement. Despite good intentions, lack of time, resources, and capacity have sometimes created hurdles too great to overcome. But challenges can lead to great innovations. I profile three examples below.

Innovation #1: Embedding transparency in traditional processes

The conventional legislative process offers many opportunities for citizens and stakeholders to provide input. A good example of this is the consultation process around Bill C-59 – An Act respecting national security matters, which employed exceptional levels of transparency and engagement.

By nature of the work itself, discussions on national security needed to balance sensitivity of the topic against providing Canadians with an opportunity to provide views on this important issue. The approach taken embodied the government’s desire to be transparent.

By way of a ministerial mandate letter – published online for the first time – the Minister of Public Safety was given the task of repealing the existing national security legislation and introducing new legislation. As a starting point, Public Safety Canada published a paper intended to prompt discussion about Canada’s national security framework. This was followed by a “what we heard report” that summarized the comments received. All the consultation feedback was then published on open.Canada.ca – a best practice that others are now emulating.

The legislative process is designed to support transparency throughout. In the case of Bill C-59, the full text of the draft legislation, tabled in June 2017, is available on the Parliament of Canada website. After public debate in the House of Commons, the Act was referred to the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security for clause-by-clause consideration, which citizens can watch online. Experts and stakeholders, including public officials, were invited to provide written or verbal statements to the Committee. Meeting dates are publicized, and often available via live webcast.

Canadians can follow the legislation as it moves to second reading, and eventually, possible adoption of the Bill. A clear thread can be seen from the start of the consultation process through the changes along the way resulting from feedback provided by hundreds of interested Canadians.

Innovation #2: Engaging to better understand the problem and priorities

Engaging early and often is key to success. But exactly when and where do you start? Should government officials draft a paper or policy to which people can respond? Or should they first ask for input in setting direction from the people whom the policy is meant to serve? Consultations with young Canadians on a proposed Youth Policy went with the latter. Many would consider this a risky proposition. What if nobody engages? What if none of the suggestions fall within the jurisdiction of the federal government? What if people post inappropriate videos or comments?

To get the ball rolling in the right direction, the Youth Secretariat posted links to examples from other countries, relevant statistics, and existing programs. Young people, and those who care about them, were invited to comment or submit videos on a list of issues that they care about, or provide one if a topic was missing! This allowed them to understand the problems and priorities from youth themselves in order to get a better sense of where the government could best meet their needs.

Innovation #3: Using solutions geared to the audience and topic

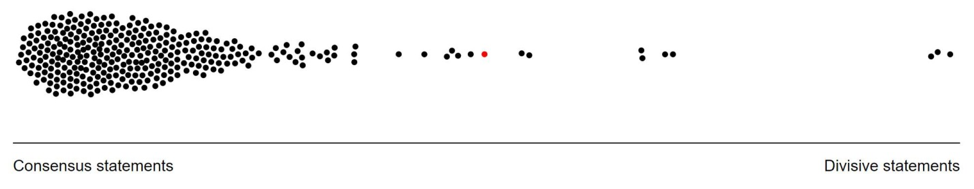

Many governments are adopting digital means of engaging citizens. Social media platforms are often used for point-in-time conversations. However, a key challenge in using online platforms is that certain viewpoints can dominate, while others remain unheard. Trolls, bots and echo-chambers abound.

When Canadian Heritage designed open source software for its Visual Arts Marketplace Engagement, it had these challenges in mind. Participants had the option to add a statement or vote on an existing statement added by someone else. A visual map revealed patterns, convergences and major points of contention in the diversity of opinions provided. Rather than reducing complex issues to simplistic views, it helped untangle the complex policy landscape. By using open source software, they were also able to modify it to meet their needs – adding automated machine translation to create one bilingual conversation.

Not everyone we want to reach is online. Global Affairs Canada used a different type of technology to reach their target audience – radio! They used it to ask rural farmers in Tanzania about their needs during a review of Canada’s international assistance framework. Internally, they used a wiki to disseminate information to the nearly 200 staff involved with the International Assistance Review.

Environment and Climate Change Canada recognized the importance of place during the Ottawa River Watershed study; people could upload photos and comments to a map of the area.

These choices highlight what this innovation is about – methods that match the channel to the audience and objective.

Where to next?

We’ve come a long way in a short time, but there is still a long road to travel to bridge the gaps between citizens and their governments.

Communicating more clearly with citizens about how their feedback is used may further increase participation. The decision-making process is often seen as a “black box.” The public and stakeholders don’t have a clear view of how their input is translated into action. Governments must clearly show how they use feedback from citizens when developing public policy outputs.

Research suggests that increasing the civic literacy and participation of citizens could strengthen democratic resilience. Governments could step back and instead support citizen-led participatory processes. We must devise new partnership models focused on outcomes. In addition to new partnerships, governments must reach beyond the people we typically talk to and support the participation of those who may have fewer credentials, but a wealth of lived experience.

Governments must invest in ongoing relationships. This is particularly critical to renew the Nation-to-Nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples living in Canada. New skills and cultural competencies are required. The timelines for consultative processes and decision-making must build in the time needed to forge relationships.

International organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Open Government Partnership are looking to Canada with great interest – connecting us to other countries so that we can share and learn from each other. If you want to connect with us, join the Public Engagement Community of Practice by emailing consultation@pco-bcp.gc.ca.