With the inexorable expansion of internet, and the advent of highly efficient computers and software, the private sector has successfully exploited “crowdsourcing,” a concept coined to describe a new approach to find talent and put it to work. Typically, the label has been given to a strategy where a firm seeks services from anonymous members of society who, in turn, will donate time and effort under certain conditions.

Crowdsourcing? Towards a Hard Definition

Although it has been changed dramatically by technology, the idea of the state relying on citizens for services is not new. Governments in all areas and at all levels have at times used this instrument to recruit soldiers, firefighters and searchers or to help informants report malfeasance anonymously.

Daren Brabham, of the University of Southern California, called for a much more disciplined use of the word in his 2013 book Crowsdsourcing. He emphasized that crowdsourcing was a power-sharing relationship between an organization (he only considered private sector corporations) and the public. He identified four key ingredients: 1) an organization that “has a task it needs performed”; 2) a community willing to do the work; 3) an online environment that allows the work to take place and, 4) “mutual benefit for the organization and the community.”

Brabham’s interpretation even prompted him to reject the inclusion of peer-produced projects such as Wikipedia (often seen as the poster child of crowdsourcing) because of its absence of a clear lead in the project, an actual commissioner of the work. Much of Brabham’s restrictive use of the term “crowdsourcing” should be adapted to the public sector—the notion of a governing authority, the availability of an anonymous community willing to do work, and the notion of a “mutual benefit” in particular—in order to distinguish these activities from others and to define their place in the inventory of state instruments.

Brabham’s tight definition has to be welcomed as governments consider new instruments to reach public ends. Crowdsourcing is not the act of making data available. Whatever services or “apps” are developed from it by the private sector stay in private hands: government cannot “crowdsource” something it does not own.

Others have used “crowdsourcing” as a synonym for consultation. Governments have long sought consultation with the public. Using a computer does not instantly make an ordinary consultation into a “crowdsource.¨

Finally, “crowdsourcing” has been used to re-label fundraising through the use of the Internet. Again, the only transformation in this instance is technological, not the act itself: the contributors are known, the sums they have contributed are known, but their choices have not affected the outcome beyond the size of its final “gift”.

Regardless of the form of crowdsourcing, anonymous individuals have shown that they can provide a valuable service to the state. They collectively can bring an intelligence, skill or effort to a wide variety of tasks. They can juggle and test ideas, and can draw attention to new sources of information.

Types of Crowdsourcing

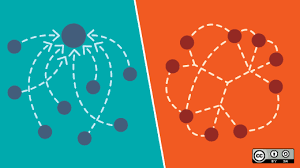

There are three broad categories in crowdsourcing:

“Crowdcontests” involve using the internet to create a competition to generate either a new idea or get people to test a product. Typically, the exercise ends with a winner (or a series of winners) who will receive some compensation for their effort. For example, in the United States, Challenge.gov inventories all of the government’s challenge and prize competitions. These include technical, scientific, ideation, and creative competitions where the U.S. government seeks innovative solutions. Canadian governments have seldom used this tool.

“Macrotasking,” applies when the Internet is used to attract and identify individuals with specialized skills and then contract with them to perform certain tasks, both physical and intellectual. In this case, as in the first, the internet was used to find (or “source”) expertise; but no “winner” is named. Canadian governments have done a good deal of work in this regard.

– Many municipalities, for instance, have crowdsourced the work of “spring cleanups” to restore their parks and common areas after the long winters.

– Library and Archives Canada has “crowdsourced” it Project Naming program. This is an effort to tie names to photos taken of the Inuit in the Northwest Territories in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s.

– The Ontario Ministry of the Environment’s enlisted citizen-scientists in helping governments collect data award-winning “Lake Partner Program” was put this into practice for over twenty years.

– The city of Richmond Hill inaugurated a Road Watch Program in 2002 to monitor traffic and to collect information.

“Crowdfunding” when the internet is used to raise small amounts of money from multitudes of donors for particular projects. As in the first two, the Internet is used to access a broader range of like-minded individuals scattered across the territory (or indeed the globe) who likely would not be aware of the need. Crowdfunding is used to ease fundraising for charitable causes but also increasingly to direct priorities.

– The Government of Canada innovated has used crowdsourcing to direct the amount of money it sends to disaster stricken countries as grants-in-aid by “matching” private citizen donations to registered charitable organizations working in specific countries. This is not an exercise in merely raising money, but in using crowdsourcing to shape policy (in terms of the size of the financial contribution).

– The Canada Culture Endowment Fund (originally Canadian Arts and Heritage Sustainability Program) has matched funds donated by community members.

– In Quebec, Placements Culture has matched donations to arts projects up to $250,000 (Government of Québec and community foundations launch generous matching grants program).

– British Columbia’s The British Columbia Arts Renaissance Fund has matched donations up to the limit of $350,000. As with CIDA contributions abroad, the departments have demonstrated a willingness to share with the “crowd” in deciding the final level of contributions.

The key feature in a crowdsourced activity is that the State is yielding important parts of the policy cycle. While it may set the agenda (though most often it does not) and will set the parameters of a policy or program, the implementation of the projects and its outputs are dependent on the crowd in this governance-sharing mechanism. In effect, the state is also committing itself to follow the lead of citizens in allocating government contributions to international aid or to cultural/artistic entreprises. This is potentially transformative of the relationship between the state and the citizen who, through this process, not only sees himself as an agent but as a partner of the direction the government will take.

Certainly, crowdsourcing has offered clear benefits. In addition to tangible help (representing the savings of incalculable sums of money) crowdsourcing has also opened for government a new form of community building. While crowdsourcing could apply to many aspects of government activity, it would not apply to all. It yields many goods, and has the merit of not being coercive—only volunteers will join the crowd—but its output is entirely dependent on non-state actors. To ensure success, the state must be diligent and the public service must deploy inventiveness and imagination.

Governments have been experimenting with various forms of crowdsourcing and from their early experience a number of lessons can be drawn. First, crowdsourcing has worked in that it allowed tasks to be performed at a much lower costs than if the state had to pay for it. Governments have proven that they could define the tasks with clarity and make use of the labour offered voluntarily.

States have also learned from the crowd and improved their efforts over repeated attempts. Crowdsourcing will not replace the state. Crowds have little sense of mission beyond the task at hand, and cannot be relied upon to strategize on behalf of the state. Moreover, crowds can be unruly, uncooperative and plainly incompetent. Their use (and usefulness) will depend on the state’s ability to marshal them in the right way for the right tasks at the right time. The task of motivating (by making it fun, challenging or pointing to a public good) and recognizing/rewarding (through prizes and distinctions) will assume a greater part of the state’s concerns.

Suggested Reading

Patrice Dutil, “Crowdsourcing as a new Instrument in the Government’s Arsenal: Explorations and Considerations” Canadian Public Administration, September 2015.