The shoe that fits one person pinches another. – CARL JUNG (1933)

Frameworks cannot be seen as global Band-Aids. Governments use frameworks as guidelines to achieve public policy, service, and administration objectives.

When considering public management issues, there is a propensity to apply established frameworks to solve complex problems. It is presumed that what worked once can produce successful results in another situation. Framework construction inherently reflects the architect’s biases. Implementation feasibility and budgeting depend invariably on political agendas. In the normative view, there is an assumption that frameworks are consistent in application, hence achieving predictable results. Conversely, in the neo-liberal view, frameworks should incorporate contextual references focusing on culturally sensitive target population assessments.

In April 2000, the UNESCO World Education Forum held a big conference in Dakar, Senegal, with the objective of providing the right to education by 2015. The Dakar Framework for Action was supported by 182 of the 193 countries attending the conference. Its adoption marginalized impoverished countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as nations in conflict. It failed to address disparate contextual layers of political, economic, social, and technological impacts in the face of growing poverty and debt levels. A universal framework, when applied as a prima facie solution to a country’s complex public management problems, is doomed to fail when it neglects resounding contextual inequalities.

Success of the NPM model

In the 1980s and 1990s, many developed countries adopted a new method of public administration called the “New Public Management”. The NPM model attempted to integrate managerial and market-based approaches in administrative doctrines to address public management problems. The key elements of NPM included decentralization, privatization, contracting out, performance management, and performance contracting.

While NPM generated modest results when transferred to some developing countries, overall success in the third-world context was limited. According to a 2003 Economic Commission for Africa study, the International Monetary Fund arrogantly relied upon NPM as a panacea for developing countries and ignored a plethora of unique contextual issues like accountability, transparency, and corruption.

Contextual approaches matter

Can managing chronic water crises in Sub-Saharan countries using Canadian public policy frameworks for water exploration, collection, sanitization, and distribution be successful in providing water to marginalized communities? In October 2016, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe attempted to promote “best practices” using a global framework. It addressed issues of sustainable consumption and production relative to resource efficiency, climate change, recycling, and hazardous waste. North American “best practices” were adapted from the United States experience.

The Universal Basic Education Policy Implementation questioned why policies regularly fail in Nigeria. Between 1960 and 2007, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission estimated US$500 billion of corruption in Nigeria. Clearly, context matters.

Proponents argue that frameworks are essential components of effective public management solutions. They rationalize that frameworks provide a set of procedures and structures that, when applied in combination with meaningful analysis and empirical data, result in consistency.

Conversely, when these inherently flawed structural and analytical decision-making frameworks are applied universally, they often fail owing to the:

- Biases of framework architects;

- Uniqueness of target populations;

- Cultural variations; and

- Collaborative shortcomings in relations with key actors.

Should flawed public management frameworks or models be exported to address international, or even subnational, problems?

Paradigm shift needed

Van Olmen et al. (2012) contend that, “… theories and frameworks are developed in reaction to one another, partly in line with prevailing paradigms and as a response to very different needs.” Bruno Jobert (2006) claims that frameworks are more than just “frames” since they come with instruments that “work” towards achieving goals.

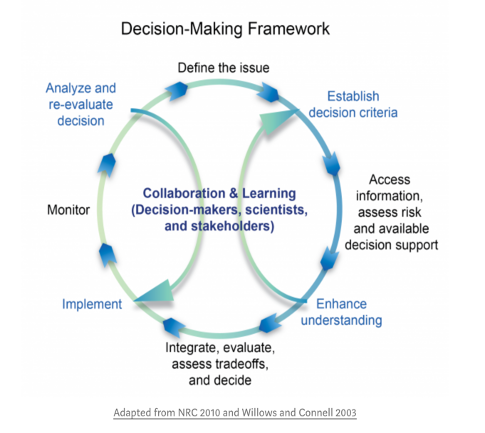

Frameworks should not take for granted the target population that they intend to address. Meaningful frames of reference should be used. Otherwise, the diffusion of influence is the consequence. Strategic collaboration with key political and bureaucratic stakeholders is essential to gaining systemic commitment from those in authority and control.

The idea of “one-size-fits-all” approach is elusive. Frameworks should be about finding “best fit”, not transferring “best practices”. The challenge of “best fit” contextual frameworks is to develop viable, multi-stakeholder partnerships that are grounded in transparency, evidence, and public value.