Do Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs) make a difference? Our evaluation shows they do. LMDAs were introduced in 1996 under Part II of Canada’s Employment Insurance Act and represent Canada’s largest investment in labour market programs. They are bilateral agreements that govern the transfer of about $2 billion annually from the Government of Canada to the provinces and territories. This money supports the design and delivery of employment programs and services best suited in each of those areas. The agreements are aimed primarily at helping unemployed Canadians who are Employment Insurance-eligible find and maintain employment.

LMDA programs can take several forms, including:

- financial assistance for training;

- services such as counselling, job search assistance and individual case management;

- job creation partnerships;

- support for self-employment; and

- wage subsidies encouraging employers to provide on-the-job work experience to people they would not otherwise hire.

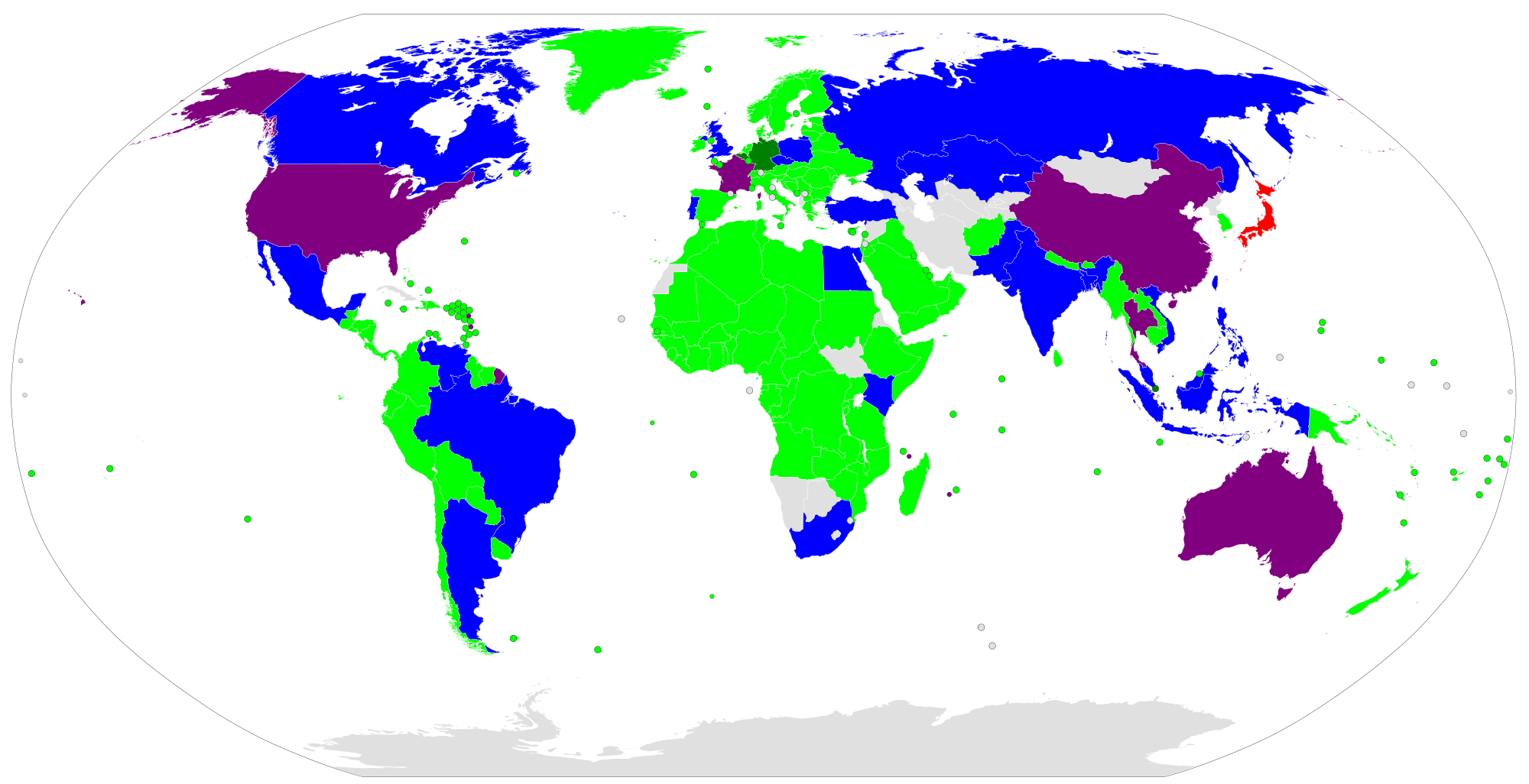

Close to 700,000 individuals received assistance under the LMDA programs in 2014-2015. Provinces and territories have full responsibility over the design and delivery of LMDA employment programs, as long as they correspond to categories defined in the Employment Insurance Act. For perspective, Canada’s active labour market programs are similar to those delivered in other countries (Gunderson 2003).

The Evaluation Process

An innovative governance model was created for the evaluation process by a collaborative, cross-jurisdictional evaluation team of federal, provincial and territorial officials. Each jurisdiction developed a quasi-experimental approach to measure the impacts of these programs, using state-of-the-art econometric techniques. They also followed participants for up to five years after interventions. The evaluation team also identified the cost-efficient opportunity to leverage three decades’ worth of existing Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) administrative data.

It is worth noting that the use of administrative data for evaluation is not new at ESDC. Over the years, the department has adopted strict rules to maintain the privacy and security of the data by masking and replacing personal information e.g., social insurance numbers by sequence numbers.

The anonymized data collected covered 100 per cent of LMDA participants and up to 20% of Employment Insurance claimants who had never participated in the LMDA programs, with the latter data used to create comparison groups. This rich data provided a wealth of historical information on participant and non-participant earnings, labour market attachment, and socio-demographic characteristics before and after participation. It enabled a robust calculation of impacts directly attributable to the participation in Employment Benefits and Support Measures. Detailed results were provided for two types of participants:

- active claimants: those who started an intervention while collecting Employment Insurance benefits; and

- former claimants: those who started an intervention up to three years after the end of their Employment Insurance benefits.

Net impacts were calculated for each of these groups on their employment, additional earnings, reduced dependency on income support programs (Employment Insurance and Social Assistance), as well as overall social benefits, encompassing participant and government perspectives.

The chart below shows that program participants have a higher probability of being employed than non-participants.

Findings at the national level indicated that the social benefits of participation exceeded the cost of investments for most interventions over periods varying between less than two years and about ten years, as shown in the table below.

The evaluation also identified which interventions worked for which groups of unemployed, and the importance of early intervention. Provincial and territorial results are being finalized. In addition to providing high-value findings, this evaluation informed discussions towards the modernization of Canada’s labour market transfer agreements.

There were other factors enabling the success of this evaluation. Senior management supported investments in a strong internal capacity and the availability of well documented and rich data. Additionally, a panel of academic experts was mandated to review methodologies and results. This panel confirmed the reliability of the impact estimates, and helped evaluation users gain confidence in the value of the results.

Impact on the Department

The new evaluation process has resulted in nothing less than a culture change within ESDC. The evaluation partners had raised concerns earlier about the first round of evaluations on program effectiveness, because results were neither prompt nor national in scope. Specifically, Bourgeois and Lahey (2014) reported that the lack of evaluation timeliness in general at ESDC had often been a barrier to its use; some academics and other stakeholders had misgivings about the overall accountability of LMDA program results and the fact that no national level assessment was available (Canada House of Commons, 2015).

In response to these concerns, ESDC evaluators improved the planning of their work in recent years. An internal capacity was created to have evaluations conducted in-house, with international experts only used for peer reviews. Evaluators continuously adapted the scope of evaluations to better serve the needs of policy makers. Regional and operational perspectives in policy research, analysis and implementation issues were taken into account.

The flexibility that was built into the evaluation process and the ongoing sharing of information with policy makers ensured that the results were leveraged in support of decision making. This work also inspired recent net impact analyses of other programs and has become the gold standard in program evaluation at ESDC.

The success of the LMDA evaluation provided another convincing argument that investing in quality data can lead to important advancements in measurements of results in the area of human capital investments.

Finally, the innovative, multilateral LMDA evaluation work has provided an opportunity for provinces and territories to regroup and collaborate on best practices. This effective partnership will enhance collaboration in the area of labour market policy and programming – a critical strength in the context of continued pressures to assist displaced workers affected by technological and global economic changes. This contributes to better policies to improve the functioning of labour markets in Canada.

Yves Gingras is Head of Evaluation, Employment and Social Development Canada. The views expressed in this article are his own and should not be construed as government policy.