Compared to audit professionals and their preoccupation with “independence”, evaluation specialists may seem unconcerned about ethical principles. Their fixation is on systematic processes, methods and techniques. Principles underlying evaluations rarely come up in evaluation planning or implementation, and they seldom figure in evaluation reports or follow-ups.

Give a workshop to evaluators on “big data” or “data visualization” and you can fill an auditorium. Have a session on evaluation principles and ethics and the room is mainly empty. So, what’s going on? Perhaps the absence of discussion leads evaluators to conclude that ethical challenges do not exist. They then infer that they and their field must be, by their very nature, principled and ethical. Suspecting that it’s not that simple, we feel it’s time to ask: What dialogue on evaluation principles and ethics ever occurs? What ethical challenges are evaluators encountering? What are they doing about them?

As are any professionals, evaluators are first and foremost defined by the central values they hold. If their central tenets go unnoticed, then their practice fades into a parade alongside every other activity in the scientific management field. Indeed, no profession is immune from this risk. For example, a study of almost 1000 physicians in several countries found that although they were aware that their profession had a code of ethics, almost to a person they admitted to not referring to it and not using it. The time is right for the Canadian evaluation community to have a robust and vital discourse on the ‘ties that bind’ us together as professionals, and that set the stage for principled practice. In the absence of such, a key cornerstone of evaluation excellence may begin to erode.

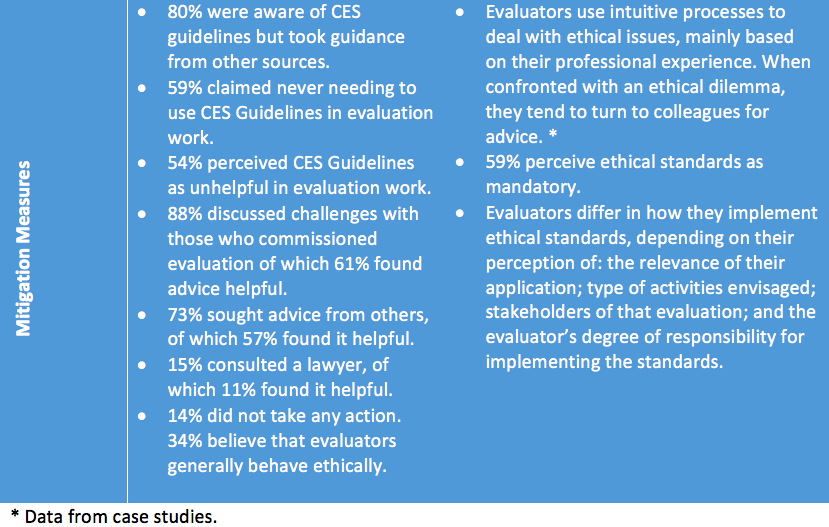

To understand how evaluators implement ethics in their day-to-day practices, surveys were conducted of Canadian Evaluation Society (CES) members in 2010 (response rate 26 per cent, n = 455) and 2015 (response rate 12 per cent, n = 218). The 2015 study included qualitative case studies of eight evaluations conducted between 2013 and 2016. See below for a summary of the results from these studies.

Ethics is a serious issue for Canadian evaluators. They associate ethics with ideas about integrity, quality and impartiality, values that are important to them as professionals. Start a dialogue about principles and ethics with evaluators and it quickly descends down a long chute of abstract concepts – accountability, competence, confidentiality, impartiality, independence, integrity, neutrality, objectivity, subjectivity, and the list goes on.

Comparing the 2010 and 2015 surveys suggests that evaluators are becoming more aware of and can identify more challenges in their work. As the 2010 and 2015 studies attest, the power of those who commission evaluations and their influence over evaluators’ treatment of ethics during the evaluation process is substantial. Evaluators are frequently called upon to deal with direct pressures from stakeholders to modify the evaluation process or findings. This can lead to potential bias in the evaluation, especially in terms of impartiality. It also increases evaluators’ anxiety. Evaluation clients, those who commission evaluations, and evaluators themselves hold important roles and responsibilities with regard to ensuring principled, ethical practice.

At the same time, evaluators seem shy to speak out on this topic. This has much to do with sensitivities related to conflicts of interest that are perceived to affect employment circumstances and opportunities. While evaluators do welcome occasions to provide feedback, there is a profound sensitivity around full ethical disclosure.

The 2010 survey revealed that three-quarters or 77 per cent of Canadian evaluators encountered at least one perceived ethical challenge in their work, but only 57 per cent were willing to provide a description or example. For them, the setting for such a discussion needs to be right, and the space safe. Both the 2010 and 2015 studies reveal that colleagues (professional evaluators or otherwise) are an important source of reflection and advice, i.e., a trusted viewpoint in a safe space.

As participants in the 2015 study observed, discussion about ethical challenges in evaluators’ daily practice is not systematic. It raises the question of the extent to which evaluators can and feel comfortable raising these ethical issues with the client before, during, and or after the evaluation process.

The 2010 survey also revealed that there is room for a more active role from the Canadian Evaluation Society at 62 per cent. A vacuum currently exists and is something only the national association can fill. This may include professional development – workshops, formal training; regular surveillance among members; greater emphasis on ethics in the Credentialed Evaluator designation; more space in professional publications (e.g. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation), and more dialogue at chapter level events and national conferences.

The Canadian Evaluation Society is indeed now taking on this role, starting with a review of its now 20-year old Ethics Principles of Competence, Integrity and Accountability. Since that document was produced, there have been major changes in the environment affecting Canadian evaluators’ work, including the introduction of national and provincial privacy legislation; the publication of the Government of Canada’s Tri-Council Policy Statement on research with Human Participants and its exclusion of program evaluation from ethical reviews; the publication of the CES Competencies for Canadian Evaluators, and its soon-to-be-released with a renewed focus on ethics.

Other national associations, notably the American Evaluation Association and the Australasian Evaluation Society, are also undertaking ethics renewal initiatives. As Harry Cummings, CES President noted, “Evaluators’ work, roles and fundamental obligations to their clients, program beneficiaries and society are only becoming more complex, and ethical challenges more subtle and intersectional. CES needs to step up and assume leadership in supporting and protecting Canadian evaluators and evaluation stakeholders in ethical practice.”

The Canadian Evaluation Society, National Capital Chapter (NCC) will be holding its Annual Learning Event in Ottawa on February 13, 2018. The theme of this event is Principled Evaluation: Should I give a s*#t? This title is admittedly provocative but one that will delve into the questions and concerns raised in this article.

To learn more or to register for this event, go here.

Wayne MacDonald MA, CEP – Director, Canadian Evaluation Society – National Capital Chapter and President, Infinity Consulting and Legal Services (ICLS). Wayne.macdonald@rogers.com

Emilie Peter, PhD – is a recipient of the Joseph-Armand-Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarship (SSHRC, 2013) and recently completed her PhD in Public Administration at the École nationale d’administration publique (ÉNAP). Emilie.peter@enap.ca

Natalie Kishchuk PhD, CE, FCES – Vice-President, Canadian Evaluation Society and independent consultant located in Montréal, Québec. vicepresident@evaluationcanada.ca