As Canadians prepare to fill up their tax forms this year and dutifully turn over part of their hard-earned money to the government, it’s worth noting that some individuals and corporations will manage through various tax evasion techniques to pay the taxes there are supposed to.

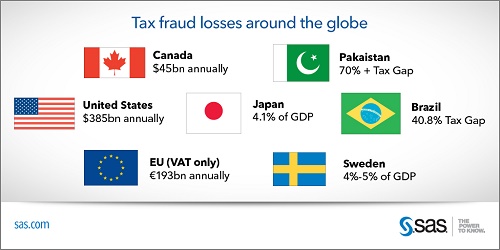

An estimated $81 billion is lost to tax evasion each year, according to the Tax Justice Network, an independent, international network that conducts research, analysis and advocacy in the area of tax evasion. According to some figures, Canada also loses some $45 billion due to tax fraud.

That’s money that could have been spent on various services such a healthcare, education, housing or seniors’ pensions.

One of the key problems governments face in tackling the multi-billion dollar problem of tax loss is the lack of resources to cope with the massive amount of data crunching involved in uncovering “connections” behind the elaborate networks used by tax evaders, according to Carl Hammersburg, senior solutions architect, government fraud at software company SAS.

Many revenue agencies are stuck on using largely manual processes in sorting through documents in order to verify the veracity of tax returns but such methods can be enhanced through automation and the use of analytics solutions that will yield massive fiscal returns, he said.

“The traditional man-to-man auditing can take very long,” Hammersburg said. “Very often, by the time fraud is discovered falsely claimed tax refunds have already been received and unscrupulous tax preparers have already gone underground.”

The toll on government coffers is huge. For instance, he said, the tax gap in the United States is around $385 billion each year. One of the methods favoured by criminals is using identity theft to assume the identity of another person in order to claim that person’s tax refund.

In the European Union, countries lose an estimated €198 billion each year due to fraud related to value added tax (VAT) refunds.

However, advanced analytics are now being used by some government agencies like the United Kingdom Tax Authority, Belgium’s VAT program, the Estonian Tax and Customs board and various state governments throughout the United States.

In 2012, the Los Angeles County worked with SAS to develop the first U.S. local government fraud detection system using advanced analytics, predictive models, and social networks to analyze, detect and prevent fraud.

Using the SAS Fraud Framework for Government, the county found more than 200 additional referrals for child care fraud and uncovered two conspiracy groups “significantly earlier than traditional detection procedures.”

A SAS fraud-detection system for the Louisiana Workforce Commission collected more than $1.2 million in improperly avoided unemployment taxes, plus penalty and interests.

Hammersburg said like the Tax Fraud Framework from SAS have been successful in helping authorities quickly identify potential tax fraud networks in a matter of minutes as opposed to days or months.

“Imagine a single person in a tax department will spend approximately 10 hours in a single case. It would take weeks, even months to recognize the structure or a network,” according to Hammersburg. “With the Tax Fraud Framework, that same person can complete the work on a single case in about two minutes.”

The analytics engine of the Tax Fraud Framework essentially searches for two sorts potential fraudulent connections: simple linkages; and complex linkages.

In investigating simple links, the solution focuses on peer links and what Hammersburg calls “outliers.”

“This could be a person living in B.C, but filing in Montreal, or members of the same family using a different tax preparer, or a business that had a sudden hiring spree but could not show any profit,” he said. “Although there may be nothing illegal, these could be red flags to potentially fraudulent activity.”

The investigation of complex linkages focuses on networks.

“This type of investigation looks into the ‘who and why’ a person is connected to certain tax preparers,” Hammersburg explains. “Over time, you’ll begin to recognize patterns. The same addresses are used over-and-over again, or multiple people from different locations are sharing the same bank account.”

These connections are often uncovered through traditional methods as well but not as fast.

“By the time authorities figure out what’s happening, the refunds have paid and the money is already on its way out of the country,” said Hammersburg.