Ten years ago I was a young entrepreneur selling processed seafood out of a factory in Vancouver. After only three years, my business partner and I had accounts with over forty stores, including Whole Foods and restaurants attached to celebrity chefs.

On one chilly November afternoon, an officer from a Federal government agency came to visit and offered me a grant and a loan. I had never dreamed of that much “free” money in my life. The only catch was that the funds had to be put towards investing in an upgrade of my facility. After many calculations and sleepless nights, I turned down the offer. I could not take the leap and expand the business. Three years later, the business closed down. (I did decide that this agent had a most interesting job, however, and joined the public service shortly thereafter.)

I retell this story every four months to a new cohort of co-op students from some of the most notable post-secondary institutions in the country. So far, not a single student has been able to give me a satisfactory answer as to why I, and Canadian business people in general, tend to underinvest in their entreprises.

The issue of business underinvestment is a critical one for Canadians. Less investment means less capital per worker and that impedes productivity, competitiveness, and innovation. Less growth also means less tax revenues for governments to pay for economic, social and environmental priorities.

So why do Canadians businesses consistently underinvest? My students with a political science background typically see this as a symptom of Canadians having been infected by the Canadian “risk-averse” culture. Those with business training—the MBA, CFA, CPA crowd—often come to the conclusion that Canadians don’t have enough business education. Economics students generally come up with the most elaborate responses. They postulate about the financial incentive to invest, unrealistic requirements on the rate of return of investments, weak demand, regulatory burden, firm size, fretting about future tax increases, and high electricity prices.

Unfortunately, there always a consensus among us that there is something unsatisfactory about these responses.

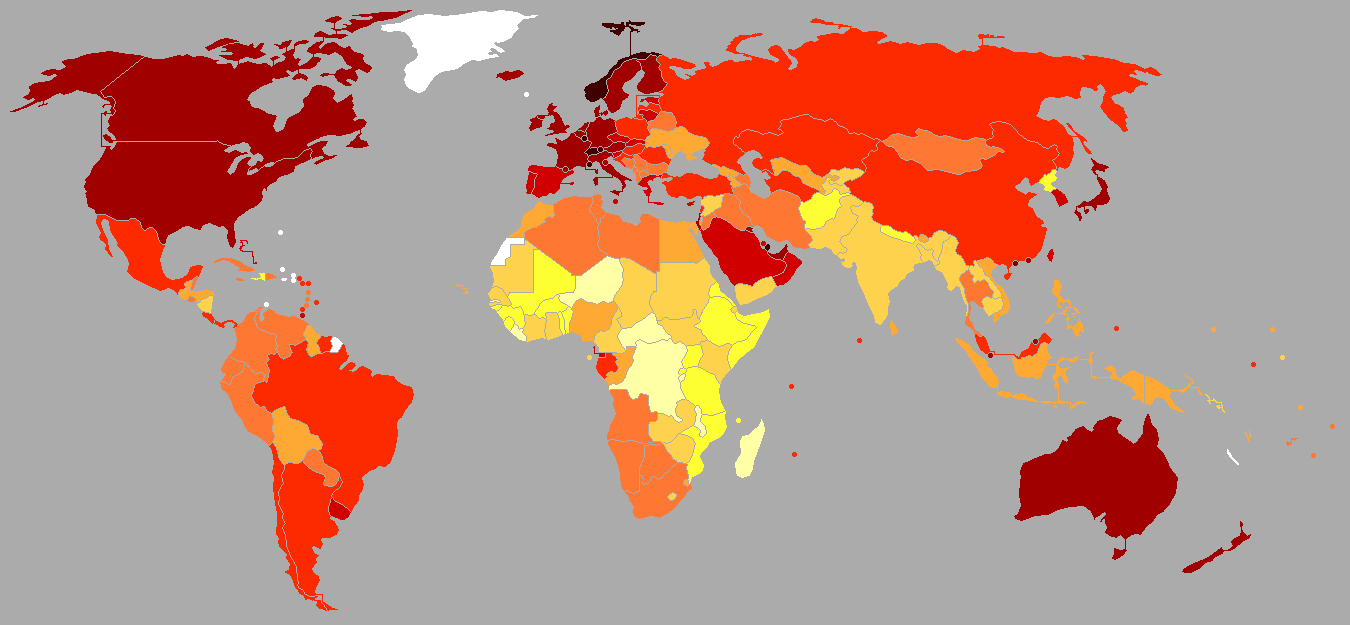

For example, there is no data to suggest that Canadians are any less educated than any other country. Quite the contrary. Canadians have the highest post-secondary education attainment in the world! And yet, when it comes to spending on the Internet of Things—the next wave, and a disruptive one, of technology—over half of top-level Canadian executives are completely unaware of this technology according to a survey conducted for Microsoft earlier this year.

When it comes to our business climate, our tax credits are some of the most generous in the world. In parts of Canada, the after-tax cost of $100 in R&D can be as low as $37! And yet in terms of R&D spending by businesses, Canada ranks 15th out of 16 peer countries. To use a hockey analogy, Canada barely makes it into the playoffs of innovation. So what is going on? My argument is that the bag of incentives provided by governments at all levels are simply not alluring enough.

On a macro level, governments across the board provide reasonable incentives: tax depreciation allowances, subsidies in the form of grants and loans, awareness campaigns, free trade agreements, reductions in regulatory burden, and investments in education.

That said, Don Drummond, the noted Canadian economist observed that during the same time that governments implemented all sorts of policies to boost productivity, productivity growth has actually slowed.

Where these approaches fall short of the finish line is that they assume that all the business owner needs is a stronger business case to invest. This is based on the assumption that business owners are rational beings.

I want to be clear that some of the policies in that list are necessary conditions for business investment. They are also critically important conditions because they form the foundation of a supportive business environment—they can encourage and incentivize business owners and leaders to at least stand on the platform and consider taking a leap. But they are not sufficient because they don’t convince most businesses to make the jump and invest.

I want to circle back to the beginning: why didn’t I take the final plunge to invest in my factory? The explanation for this was quite simple. It has nothing to do a lack of a business case. It simply came down to a business associate. Shortly after I had formed my company, he had expanded his factory but economic conditions worked against him and he was out of business. It was tragic. Thirty people were let go that day. So the rational business case didn’t matter even one iota to me when faced with the simple image in my head of my partner’s padlocked factory.

This kind of decision-making is a central theme in behavioural economics and it turns out to play a profound role in explaining a whole host of unexplainable phenomena—including how some of the brightest traders and risk managers in the world allowed the subprime housing bubble to expand for years. What behavioural economists believe, in contrast to neo-classical economists, is that psychological, emotional, and social factors have an enormous impact on how economic decisions are actually made at the firm level.

While this may seem like an obscure theory, Germany has been applying it for decades in implementing its menu of business incentives to innovate and export. Its key weapon is the Fraunhofer Society. Founded in the aftermath of the Second World War, at a time when Germany’s advanced industries were severely impaired, today it boasts 67 institutes throughout the country, spends an imposing budget of €2.1 billion and employs 24,000 people. The Fraunhofer’s primary mission is to perform contract research for German SME’s. For example, one of their key program areas enables small and medium sized manufacturers to test equipment and industrial processes on pilot manufacturing lines. In these sorts of programs, the emphasis is on a continual process of incremental improvement in processes with near term commercial impact. All of this makes a difference: Germany’s small and medium sized manufacturers are the backbone of its economy. The country’s average labour rate in the manufacturing industry is €37 (C$53) per hour.

Today there is one at the University of Western Ontario, and I recently had an opportunity to visit it. It was officially opened in 2012 with the support of $24 million of funding from all three levels of government. In collaboration with German researchers, the Canadian team has helped firms in sectors as diverse as automotive, aerospace, and clean-tech to use materials more innovatively. What really impressed me about their model was the how actively they were collaborating with the businesses—testing, researching, and demonstrating the benefits of new investments in processes and product improvements. Business owners get to touch and feel what a successful project would look like before making their final commitment. Its menu of services—in stark contrast to the offer of cold hard cash by a Canadian government employee—delivers advice, tested knowledge and know-how. It brings reassurance to the business owners/leaders; it makes the leap less scary and significantly de-risks their investment.

Our competitors are well aware of these successes. In the last five years, the U.S. and the U.K. have both made significant commitments in such organizations, totalling in the billions of dollars, in institutions that are modeled after Germany’s Fraunhofer Institutes.

What we need in Canada are two separate and distinct policy streams. The first stream would include all of those programs that enhance the business case for making investment: infrastructure, tax policies, electricity costs, broadband access, education, immigration, funding, stable macroeconomic conditions, trade agreements, and the like.

But then we need to provide a second layer of programming. I call these the “giant leap” program and policies. These would target all of those barriers, especially the psychological ones that hold businesses back from taking the critical step that will allow them to scale-up to the next level. Is it risk perception? Is it a lack of strong advocates? Is it recent and tragic anecdotes of failure? If so, we should invest in more community-based programming, trust-based mentoring, real-world demonstrations, and partnering, testing, modeling and computer simulations. A closer look at programs modeled after the Fraunhofer institutes would be an excellent start.

The good news is that Canada has a handful of excellent organizations that are already doing this. Just to take one example, Go Productivity, an organization based out of Edmonton but with a Canadian mandate, provides coaching while encouraging firms to overcome their productivity barriers as part of a supportive community. Companies that are simultaneously going through the program meet regularly, share updates on their progress, and detail successes and learnings from their projects. Much like the Fraunhofer Society, Go Productivity’s pragmatic approach can be credited to the fact that it was born out of a very pressing and immediate concern. Founded in 2008, its goal was to increase the capacity of an Alberta supply chain struggling to keep up with orders in the face of a booming oil and gas industries. Operating with a very modest $3 million annual budget, today it has worked with over 500 clients and achieved a 96% client satisfaction rate.

More research and thought leadership is urgently needed here to help the business community. The issue is not only about cash, but reassurance. Canadians do not have a problem in education or awareness or intelligence. It’s a problem of psychology. As any serious athlete can tell you, this is oftentimes the most crucial barrier to crossing the finish line.

Christopher Lau is a Senior Business Development Specialist in the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Growth