Why is strategic planning so dreaded? How often do we actually deliver what the plan outlined? Why is buy-in so low? How many retreats are show-and-tell sessions instead of true strategic discussions? Why do we find ourselves at year-end, engaged in creative writing to provide the impression that we met our goals?

A handful of departments, agencies and Crown corporations have taken a different approach and are getting noticeably better results; here are five practices that have helped them improve.

- Start with the Problem

Planning retreats are often filled with solutions and pet projects. The easy way out is to say “yes” to them all, keeping peace in the family, while overloading people, wasting resources, and diluting focus. This happens when you start with the solution, instead of with the problem. Once a group agrees on a specific, measurable problem to solve, then it takes much less effort to select and gain consensus on a solution.

We worked with an agency that pursued the solution of “Consolidate our service desks” for over five years, with nothing to show for it but a recycled PowerPoint deck. When we asked them what problem they were trying to solve with this consolidation – most executives were vague, or could not identify a specific problem. Five years and millions of dollars of consultant fees wasted. Contrast this with a similar organization that identified a key problem as “74 per cent of client contacts in 2012 were preventable. Impact: reduced ability to address value calls within 24 hours, creating an unacceptable risk for our clients.” Which organization do you think made more progress, faster?

If you identify and agree on the problem and its impact, then choosing the solution becomes much easier. Einstein said: “If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.” It feels slow to start with the problem and its causes, but as one executive at a Crown corporation said as she handed out toy turtles to the planning retreat: “we have to move slow to go fast.”

- Create Broader and Deeper Ownership

Many organizations treat strategy creation as separate from strategy execution: Senior executives, working with other executives, create the strategy, then hand it off to others to implement. This is a recipe for misunderstanding, misinterpretation and low buy-in.

I did a keyword search of publications in Amazon.com’s business book section, and found the following:

We often spend immense effort creating strategy, and the remaining effort to sell the idea to staff. Execution is an afterthought – “we’ll let the operational people figure that out”. No wonder John Kotter identifies that 70 per cent or more major projects fail to meet their initial objectives.

A better approach:

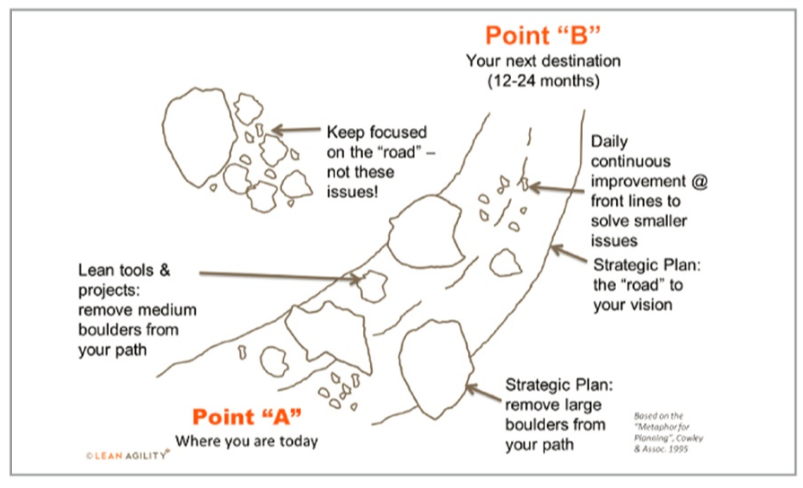

- At their retreat, executives identify on a single page: Point “A” and Point “B”, the strategic problems that must be solved along the way, causes, and rough-draft, incomplete solutions.

- They then show their work to leaders 2-3 levels below, and ask: Did we get this right? If not, what do you see? Challenges?

This is called “Catchball” like two groups tossing a ball back and forth. Senior executives focus on the “Where we are going” and “What are the gaps” and the executors focus on “How can we get there”. The benefits? A more-executable strategy with deeper ownership from the executors.

- Make the Plan Visible and Create Routines

It is hard to manage what you cannot see. Strategic plans are often buried on the intranet or in binders. A Crown corporation depicts its plan on whiteboards at multiple levels, from C-Suite to frontline staff. Each level sees how it contributes to the top-level priority, they make regular adjustments, and as they learn, performance improves. Once per quarter executives conduct what is called a “wall walk” to go, priority by priority, through their plan to troubleshoot and adjust as a group.

- Recognize true capacity and say “No thanks, not yet” to what does not fit

I asked an ADM how many priorities his branch had this year. He replied proudly: “52”. I asked him if he could recite them. He paused, and sheepishly replied “no”. Given this, is it realistic for others in his branch to execute them all? With too many priorities, focus and effort are diluted and little gets done.

A study of software coders shows what happens when humans take on too much at once and switch between high-focus tasks (context switching), otherwise known as “multi-tasking”.

How do you say “no” to less-important priorities so that you don’t fall prey to this capacity drain, without alienating stakeholders who may own these priorities?

By starting with the problems to be solved, instead of starting with solutions, groups typically reduce priorities, without hard feelings. Next, identify the “Must-do, can’t fail” / “Breakthrough” priorities, versus “Should-do”, “Could-do”, “Do next year” and “Don’t do” priorities.

To help groups understand how to narrow their priorities, consider an exercise from Greg McKeown, the author of “Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less”: during spring closet cleaning, how do you decide which clothes to keep and which to give to charity? Most people ask about each garment: “do I still like it?”, “does it still fit me?”, or “when did I last wear it?”. All good, sensible questions. But McKeown’s question is: “If I didn’t possess this exact garment, in its exact condition, how much would I pay to acquire it?” This question is powerful because it introduces the notion of scarcity: we only have so much money. Similarly, we only have so much time to implement priorities.

Using a simple method to quantify available and required capacity, most organizations realize that they have been signing up for 100 to 200 per cent more than they realistically have the capacity to execute. By identifying the capacity price tag of each potential priority, executives more quickly come to a consensus on which to keep and which to defer or abandon – and also address many execution challenges.

- Adjust as you go

A provincial Ministry of Health was able to reduce its number of top-level priorities from over 30 to 18. A regulatory Commission reduced its priorities from over 20 to two. In both cases, they actually delivered on their priorities listed in the plan. Less overwhelmed, they were able to adjust along the way to deal with political and environment-driven change. A commercial Crown corporation uses its quarterly review to re-assess capacity required, and where to redeploy capacity in order to focus on the most important priorities. Regular executive wall-walks are an efficient and effective way to check to stay on course and to be nimble enough to adjust to unforeseen challenges and changes that will always be a part of public service. As a bonus, this sends a message of the importance of continuous improvement at all levels.