Words, words, words. Blah, blah, blah.

Our days – our work lives – are punctuated by a sea of words. We use words to communicate. We use words to not communicate. We use words to share our ideas, to propel our innovation. Think of a recent meeting and you’ll likely think of blah, blah, blah.

But we can think and communicate through more than words. And a series of books in recent years have tried to help us to shift, adding a visual component to our meetings, communications, thinking and brainstorming.

Blah Blah Blah

Dan Roam

Portfolio, 350 pages, $29.95

Visual Meetings

David Sibbet

John Wiley, 262 pages, $35.95

The Back of The Napkin

Dan Roam

Portfolio, 278 pages, $24.95

Presentations specialist Dan Roam, who authored two of the books, says that blah, blah, blah is killing our ability to think, learn, work and lead. Instead of clarity, we have fog – complexity, misunderstanding and boredom.

“Ever left a meeting more confused than when you entered? Ever watched two hours of cable news and knew that you knew less about the world? Ever stifled another yawn during another conference room bullet-point bonanza? You get the picture,” he writes in Blah, Blah Blah.

He has even developed something he calls a Blah-Blahmeter to help us evaluate how bad the situation is. It has a scale – one to three blahs – for rating how miserable the situation is. The conversation, meeting or presentation is merely blah when the intent is to illuminate, the topic is complicated, and the message ends up boring. You’ve been to a lot of those sessions, undoubtedly, earnest but ineffective.

It moves up the scale of awfulness to blah-blah when the intent is to obfuscate, the idea is missing and the message is foggy. It’s blah-blah-blah when the intent is to divert, the idea is rotten and the message is misleading. By contrast, a no-blah event occurs when the intent is to clarify, the idea is simple and the message is clear.

Both Roam and David Sibbet, who specializes in graphic facilitation, believe that sharpened meetings and sharpened thinking can flow from reducing words and enhancing the visuals in our communication.

In Visual Meetings, Sibbet notes that when we think of meetings, we automatically think of words. Instead, he argues, the first thought that should come to our minds is visuals. And not PowerPoint, by the way. Instead, our meetings should revolve around a panorama of visual design, stimulating thought and recording our progress. So flipcharts, with sketches and doodles that express our thoughts in vivid fashion.

Instead of proposing an idea with blah, blah, blah you might draw it as part of a map that the group collectively creates to plot its journey together on a project. Or you might write it on sticky notes that could then be grouped on a wall with your colleagues’ suggestions.

“My confidence in this way of working is rooted in three phenomena that I have experienced since the first time I picked up magic markers and began facilitating groups visually,” he writes.

He argues engagement explodes in meetings when participants are listened to and acknowledged by having what they say recorded in an interactive, graphic way. Second, a group can think in a big picture way when their ideas are shown visually, allowing everyone to check for patterns or connections more easily. Third, creating memorable media increases the group’s memory and follow-through.

Of course, this is not totally foreign to us. Our meetings occasionally have some of these tools. But it’s occasional, while blah, blah, blah rules. He believes the visual element should be routine, a starting point to energize our thinking and the meetings.

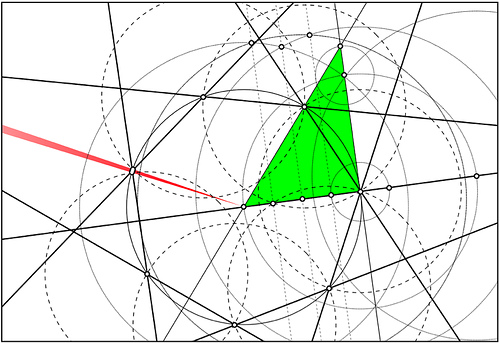

If you’re like me, you may wince, not eager to have your inability to draw be shared with your colleagues. But both Sibbet and Roam are not talking artistry. They are talking stick figures and other simple sketches that theoretically anyone of us can do. In The Back Of The Napkin, Roam sets out basic shapes like circles, squares, rectangles, triangles, arrows, straight lines, happy faces and stick figures as the basic sketching tools you will need.

The most successful airline of our era, by the way, started with a sketch of a triangle on a napkin, he reminds us. Rollin King, who was closing his regional airline, told his lawyer Herb Kelleher that instead of running a small airline that services small towns it made sense to run a small airline servicing big cities. He drew the triangle and marked the three edges: Dallas, San Antonio and Houston. It was neat and simple, unlike the spaghetti of lines that depicted the complicated routes of the traditional airlines servicing big centres, and Southwest Airlines was born.

Of course, there was undoubtedly some blah, blah, blah at that luncheon meeting. And if the sketch had not been drawn, the airline might still have been developed. But the clarity of the sketch helped to make it more appealing, Roam believes. “Visual thinking means taking advantage of our innate ability to see – both with our eyes and our mind’s eye – in order to discover ideas that are otherwise invisible, develop those ideas quickly and intuitively, and then share those ideas with other people in a way that they simply ‘get’,” he says.

Essentially, he is arguing that the shapes we draw are an extension of our thinking. He observes it’s a more balanced way of thinking, bringing together different elements of our brain. “The reason for all the blah, blah, blah is that we’ve simply forgotten how to use both our minds. For 30,000 years, humans have been making marks on walls (then on paper, and more recently on touch screens) to reflect our thoughts. For 25,000 of those years, we drew pictures. Only in the past 5,000 years did we begin the gradual shift to writing words. The problem is that now we have gone too far,” he says.

In Back Of The Napkin, Roam tells us there are six fundamental questions that guide how we see things and then how we show things. Each question has one dominant visual method – a simple-to-draw visual method – for displaying the results of your thinking:

- The who and the what: As we start to get oriented to a situation, our thinking commences with who and what. Take the example he gives a training manager who is struggling to come to grips with the many programs at her new company; for her, the thinking (and sketching) begins with who gets trained, who does the training, what topics are taught and what lessons are presented. This is best depicted visually through portrait-style sketches, perhaps a video camera to show that method of delivering programs and a number of stick figures or simple portraits of faces to represent those who will be attending a course.

- The how many and how much: Next we quantify what we have been seeing. How many lessons are required and how much time do they take? How many people can attend each lesson, and how many instructors are needed? Charts capture this aspect of the problem.

- The where: Spatial orientation follows. Where will the lessons take place? In the company’s stores, in training facilities or at home? A map can illuminate this issue, perhaps also capturing the conceptual issue of where the lessons might overlap in content, structure or intended audience.

- The when: The training manager must address when do the lessons take place and in what sequence do they need to occur? A timeline will help here.

- The how: How does one lesson relate to another? How do you know when you are ready to move on from the subject matter you are studying? Flowcharts reveal these linkages.

The why: Everything must be brought together to understand the core of the issue. This will be the most complicated chart, with a coterie of the variables displayed in one creative sketch.

So imagine your next meeting as a blizzard of sketches instead of a sea of words. Not no words, but a better balance between words and visual thinking, adding up, together, hopefully, to a no-blah zone. To help you get there, any of these books could be helpful, but I’d probably suggest The Back Of The Napkin and Visual Meetings as a combo.