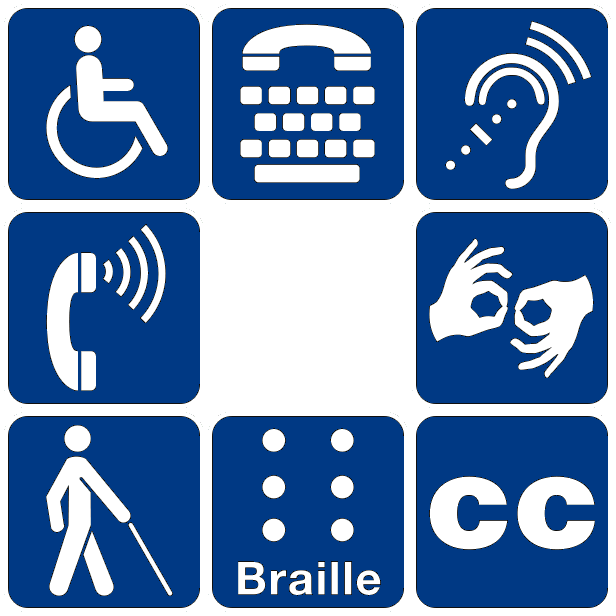

Canada has made great strides to make public spaces accessible to persons with disabilities over the past several decades. Look around your government building today and you’re likely to see many amenities to support the 4.82 million Canadians with a disability. But we must remind ourselves that our world now spans beyond the physical.

Government departments are likely well aware that their digital spaces are far less accommodating. Many local and municipal websites’ coding still isn’t fully compatible with assistive technology used by people with disabilities who struggle to read, hear and engage with websites.

This is a concern, particularly for the 1.2 million Canadians with limited dexterity, the 949,000 who are partially sighted or blind, or indeed the millions more who are color blind, dyslexic or hard of hearing. They need aids, software and devices to help them read a web page, access a document or fill in a form. If the website’s code doesn’t properly engage to those aids, those people simply can’t log in.

Rules, Guidelines and Future Laws

In 2011, the Government of Canada released its Standard of Web Accessibility, which called on all government websites to be Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 ‘Level AA’ compliant. WCAG 2.0 is the international standard for websites, created by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). WCAG 2.0 is made up of guidelines and principles with measureable success criteria at three levels (Level A, AA and the gold standard, AAA.)

Most government officials currently see this as a guideline as opposed to a hard-and-fast rule, but more robust efforts are in the works. The Honourable Carla Qualtrough, Minister of Sport and Persons with Disabilities, is currently leading consultations on the accessibility barriers Canadians face in their daily lives with a listening tour around the country, and digital accessibility is a big part of that conversation.

But the real work to implement WCAG 2.0 now is happening at the provincial level and Ontario is leading the way. The Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) is the measuring stick for efforts to level the playing field for all. The AODA’s guidelines for web accessibility are practical and attainable, they lay out a sensible timeline and all the resources in Ontario are written in a plain language. By now, all Ontario government web spaces should be at WCAG 2.0 ‘Level AA’ standard.

And other provinces are following Ontario’s lead. The Accessibility for Manitobans Act (AMA) includes the Information and Communications Standard that explicitly calls on anyone who provides services to address barriers to accessing information online, but it doesn’t specify a WCAG 2.0 standard that’s necessary to do this. Quebec’s public websites should comply with its custom-made standard SGQRI 008-01, which is comparable to Level AA. In 2014, British Columbia set out a 10-year plan to make the province accessible to all, including all online spaces. It’s moving forward well, and last December gov.bc.ca met Level AA standards.

As Rules Evolve, Pressure Builds

The problem today is that these mandates are understood and appreciated by smaller government website managers and practitioners, but they are not being met. Time, lack of resources and financial strains are all barriers facing governments that know their websites are not meeting Level AA or even Level A standards. Until now, Canadian governments have been operating under a (sensible) grace period – they are aware that web accessibility must be addressed but there’s been no impetus to put it on the top of the to-do pile or move precious resources to make it happen.

But, the grace period that most governments have operated under is coming to an end. Minister Qualtrough’s project is putting a much-needed spotlight on the issue, and more provinces are now outlining firm dates to enact standards. In short, inaccessible government websites will soon not be tolerated.

Those whose responsibilities include managing their city, region or municipal website must begin to act now because many governments are unaware of the deep and binding changes various departments have to make to ensure a website is always accessible. A website is an ever-changing document and is planned, penned, managed and edited by various people in different departments over a long period of time. To ensure everyone is rowing in the same direction takes planning and leadership.

An Org Chart For Web Accessibility Success

The best place to make change is to start with the person or persons for whom the buck stops when it comes to the website. That might be an IT manager, a marketing manager or a Webmaster. But buy-in and awareness of the issue must include decision-makers further up the ladder. Making a website more accessible likely means changing processes in various departments, so multi-level engagement is vital.

To assess a site’s inaccessibility, an online tool can be used to assess every line of code to see where the biggest flaws can be found. Finding these faults can begin conversations about website management processes and how adding accessibility considerations would affect that process, and then how the government goes about changing process for the long term.

Next step is education. For an organization that has a decentralized system of web maintenance and management, this is crucial that anyone who touches the website must understand what web accessibility is. They must be educated to understand which facets of a web page might be inaccessible to a person with disabilities and how to make sure they amend content to fix that.

It’s also important to understand how this training can be imbedded into all future web training. Making a site compliant just today isn’t helpful – all new pages and documents must always be compliant.

Best Practice: Start Small, One Step At A Time

The idea of training webmasters to learn WCAG 2.0 can be daunting, but there are a number of top-line issues website managers can begin to address immediately that will significantly improve their status and come closer to compliance.

Clean Up The Code

The first step to accessibility success is for website guardians to ensure clean, quality code. Excessive or non-compliant code, created by bad designers or bad design software may be non-compatible for assistive technology and special software. Working with a good development team to go through and clean up your backend code is vital.

Add Alternative Text

Adding alternative text for visual elements of a website is a cornerstone of good accessibility. Alternative text is simply adding a descriptive ‘tag’ to a website element, telling a user what it is. A button, an image, or anything: assistive technology will take the information that the element conveys and then ‘translate’ that into a clear and concise phrase or sentence. Simply, if any element cannot be ‘read’, then it may not be accessible to a person with a disability.

Reassess Site Hierarchy

Websites are not books or newspapers, we do not read them or navigate them in a linear way. To create an accessible site one must approach a website’s content hierarchy as web content. Headers are particularly important to make site hierarchy cohesive – websites are constructed using header tags in descending order to organize the information. Much like we visually ‘scan’ a web page, accessibility technology and software ‘scans’ a site using these tags, so it’s essential that website headers and page hierarchy is simply and correctly organized.

Fix Forms

A form can be the most complicated part of a website. They may have to interact with a database or another form and require unforgiving pieces of code. A good form should allow a user to ‘tab’ their way through, moving from one box to the next in order and fill out the fields only with a keyboard. But if a form isn’t correctly coded at the back end, it may not work for someone with a disability.

There are more issues to consider, but this illustrates how simple code changes can help persons with disabilities immensely.

Helping Millions of Canadians

On average, Canadians spend more than 36 hours a month online, more than anyone else in the world. They are also spending plenty of that time in government digital spaces. According to recent government data, more than half of Canadians regularly search for information on municipal, provincial or federal government websites and more than a quarter are using the Internet to communicate with their government. It’s fair to extrapolate from this data that millions of Canadians who have a disability are using the Internet to try and connect with and speak to their government.

At the end of 2016, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) announced that broadband Internet is a basic service that all Canadians are entitled to receive, underlining the importance of high speed Internet in our modern lives. Just as Canadians are entitled to receive high speed Internet, Canadians with disabilities are also entitled to be able to use that service and have equal accessibility to the information it provides.

Kevin Rydberg is a senior digital accessibility for Siteimprove’s Quality Assurance and Web Governance services (www.Siteimprove.com).