Rushing to keep up with deadlines but never getting ahead is commonplace in today’s public service. In traditional thinking, we never seem to have enough capacity–people, time, budget–to keep up.

There are ways to free up capacity to beat this crunch. And some of the clues are right in front of us and within our control. Unfortunately, we are so close to our work and so busy that we rarely step back to spot them and deal with them.

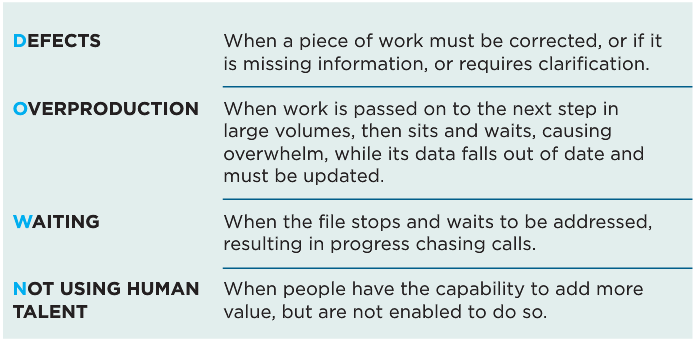

Over the years, Lean practitioners have identified a number of these clues, a set of broad categories of non-value added activities, or “wastes”. If you can understand what they are, you can take steps to remove them and free up capacity to finally catch up.

All eight of these wastes contribute to the government capacity crunch; in my experience, three of these wastes seem to consume noticeably more capacity than the others, namely, Defects, Overproduction, and Excessive Processing. In this article, I will look at examples of the waste of Defects, and note some solutions to eliminate them to free up capacity. In the next articles, we will address the other two high impact wastes.

I helped a public servant from a Federal agency use Lean to streamline her Travel and Event (T&E) approval process. The process was based on a Treasury Board directive designed to promote the “effective, efficient and economical use of public resources” on travel and events. The Directive required that a T&E request of between $ 5,000 and $ 25,000 be signed off by one of two people: the Deputy Minister or the Senior Departmental Manager. After reviewing the process the team found that the directive was successful in reducing overall expenditures on travel and events, but the effort spent creating, reviewing and approving requests was higher than ever before.

Mapping the process showed that T&E requests were reviewed and adjusted sixteen or more times before getting to the DM who then asked for clarification or requested changes on six out of ten requests. In total, over 95% of requests were returned or reworked at least once. The total effort per typical request, including clarifications, changes, error-fixing, review and re-review, totalled over 40 hours. The correspondingly lengthy approval process could result in a $400 plane ticket becoming a $1,200 plane ticket. The waste of “Defects” was prominent in this situation, consuming many more hours of human capacity than it should have.

By eliminating defects in the process, staff were able to dramatically reduce preventable work, freeing up close to 50% of the capacity previously required, on a majority of its volume. As an added benefit, this resulted in shorter lead times and thus lower airfares by avoiding last-minute booking costs.

How did they do it?

Identify and eliminate the root causes of defects: During the Lean project, the team determined that users failed 80% of the time to complete the application form successfully, causing major preventable work, because the form was:

- Written in “expert”, not common language;

- Written with overly broad questions that did not prompt or “nudge” the user into the correct answer, the first time;

- Wordy, lengthy, and not understandable “at a glance”, so users would give up and submit a hastily-completed form instead of taking the time to figure it out;

- Multiple forms for different types of requests resulted in some forms not being filled out, or being filled out incorrectly.

After running focus groups to identify the causes of recurring errors and usability of the current forms, the team was able to simplify, consolidate and error-proof them to make them intuitive and easier to use. Piloting and adjusting the new prototype forms with small groups of real, typical users, proved that they would save considerable effort and led to a successful launch. Tip: If you are trying this on your own, make sure that you run your focus groups with typical users, not your most-experienced or best users. While your “power users” might be easy to recruit, they probably have learned how to use imperfect forms. On the other hand, if the least-successful users can get the task done correctly with your new prototype form, then the prototype form will likely work for everyone.

Identify approval criteria and the percentage of time each criterion is not met: Building a list of approval criteria, and identifying what percentage of the time each criterion is not met in the first draft, allowed the team to build questions into their forms to help the user get it right the first time. This can help increase the probability that the first draft is sufficiently strong to make it through the process with minimal or no rework, saving effort.

Provide early support: As many applicants in the approval process were infrequent users, and one-time training on the process was likely to be forgotten as time elapsed, the team began providing just-in-time coaching to help users fill in the documents accurately. This may sound like unnecessary effort, but a key principle in eliminating defects is that often a small, early, investment to help a user get it right, pays major dividends, by reducing rework later. In some cases, fifteen minutes of face-to-face coaching can save ten or more hours of preventable work. The earlier a defect is caught, the lower the cost.

The lessons is clear: the later in the approval process a defect is caught, the more effort or capacity is needlessly expended. It will be then re-reviewed by more people on the way back up the chain. And the senior people who conduct the later reviews are typically less available, causing the file to sit and wait, and eventually fall out of date (e.g. airline and hotel prices change) and then perhaps require an even greater amount of rework, or even a complete re-write. As well, reviews by executives cost more, in terms of both salary and opportunity cost.

Eliminate sequential reviews: Instead of the file being reviewed by the Analyst, Manager and Director in sequence, the team submitted the draft request to all three levels at the same time and required a face-to-face review of the three of them, along with the requestor. This reduced four or five rounds of revision and re-reviewing to one single round, cutting their review/revision effort by up to 75% and lead time by up to 90%. It also forced each of the four levels to get onto the same page, learning what a “great” submission looks like so that the next request is of better quality, saving effort.

Defects, and the preventable work in addressing them, consume remarkable amounts of our capacity, but because our processes are invisible, this cost largely remains unseen. Mapping the process, quantifying defects, identifying them, and addressing them at their source can free up valuable capacity to be used to keep up, or finally get ahead. In the next article, I will look at the waste of Excessive Processing, and how it can be addressed to further free up capacity.