Lately, all levels of the Canadian public service have devoted much attention to developing effective and forward-thinking public service renewal strategies. These efforts include the Ontario Public Service of the Future: 2018 Action Plan, the Government of Canada`s Secretary to Cabinet focus on public service renewal strategies, and the Canadian Association of Municipal Administrators toolkit to recruit the next generation of municipal administrators.

Various forces triggered this activity. First, the looming wave of baby boomers’ retirements evokes images of lost organizational memory and operational expertise erosion, ultimately leading to reduced service delivery capacity. Second, the drive to innovate approaches, processes and products – that is increasingly central at all jurisdictional levels – created pressures and opportunities within the human resources area. Finally, competition among the various jurisdictions and organizations for scarce talent will create unique dynamics in the 21st Century.

The Institute of Public Administration of Canada, as part of its engagement in this area, created and administered a survey of new professionals across provincial, territorial and federal public administrations in 2015, and again in 2018. This survey explores the human resource and public service renewal approaches by engaging this key demographic.

Here we highlight some select results from these two surveys, noting, however, that the 2018 survey is still ongoing, and while we have over 5,000 answers, some of these numbers will shift. The other disclaimer is that the composition of these answers is somewhat different with much stronger Government of Canada participation in the 2018 survey. However, these are robust returns providing important indications on how this group perceives the present and future of the public service.

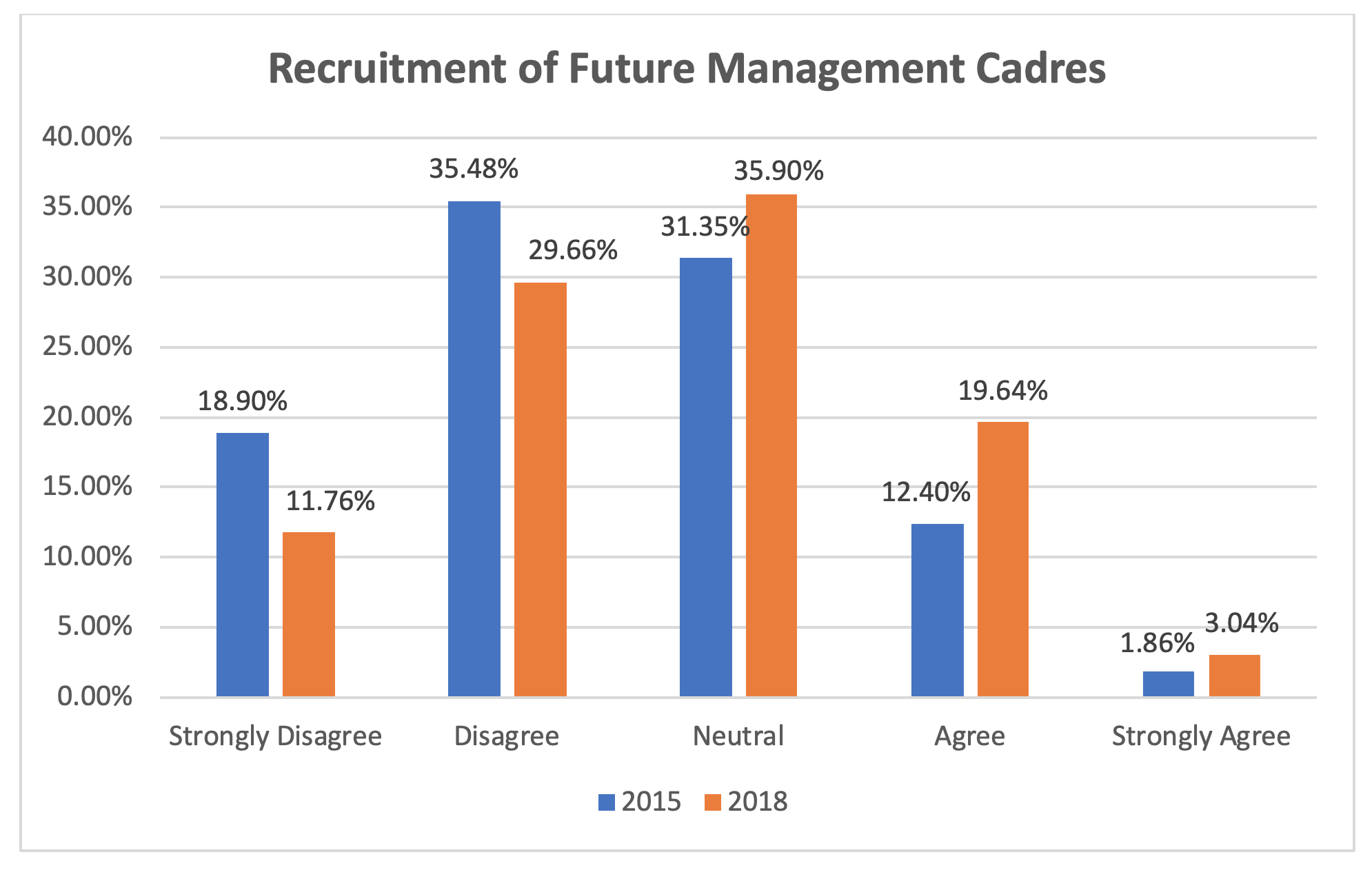

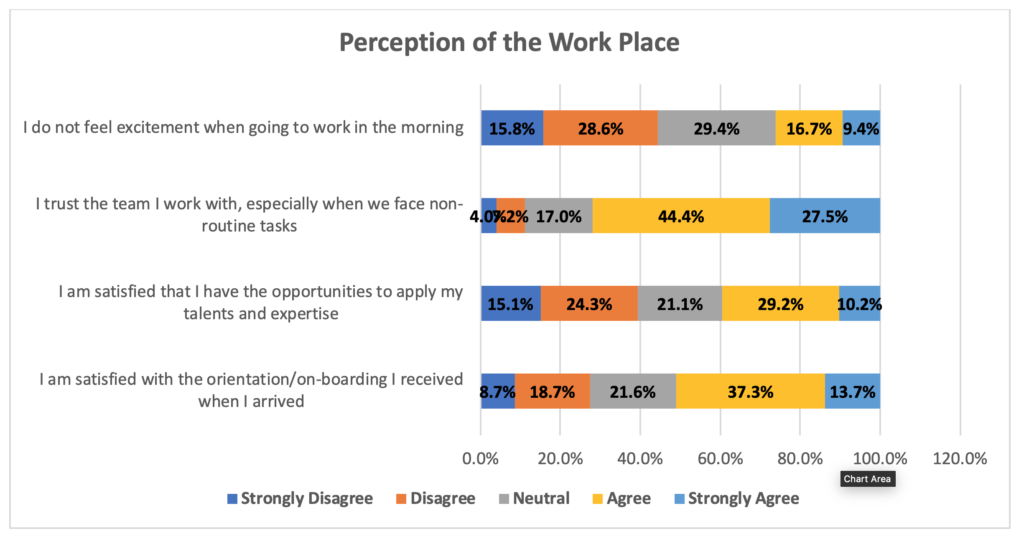

In both years, we asked new professionals if they agreed with the statement that their organization has in place appropriate programs and incentives to identify and recruit the next generation of public sector managers. We found significant improvement: 13 per cent

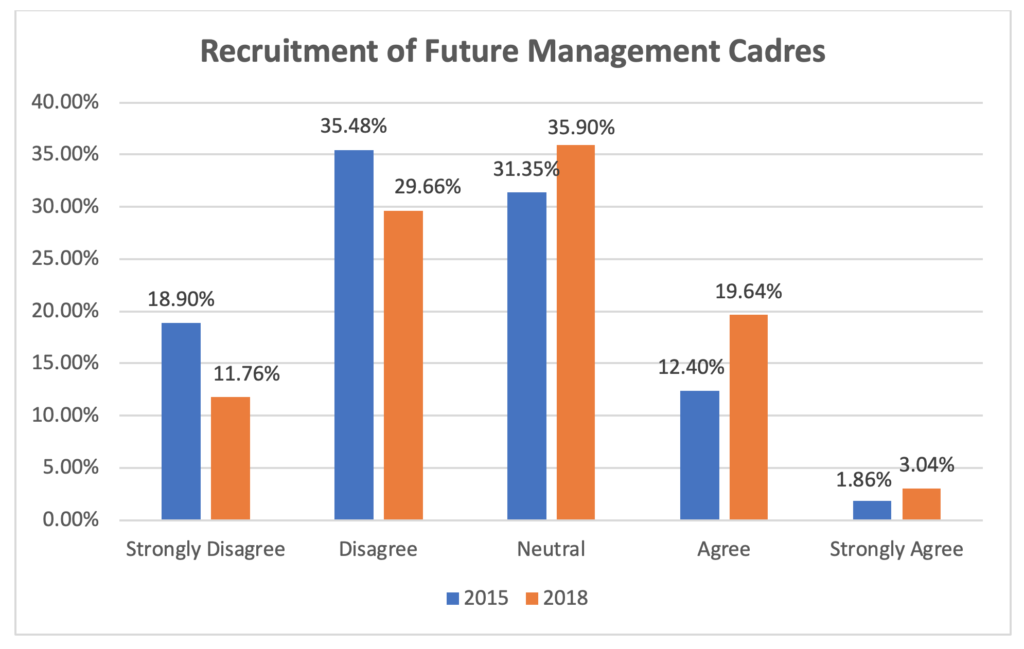

We also inquired about whether new professionals agreed that their organization has adequate systems and tools to coach and develop strong leaders and teams. Progress here is less evident.

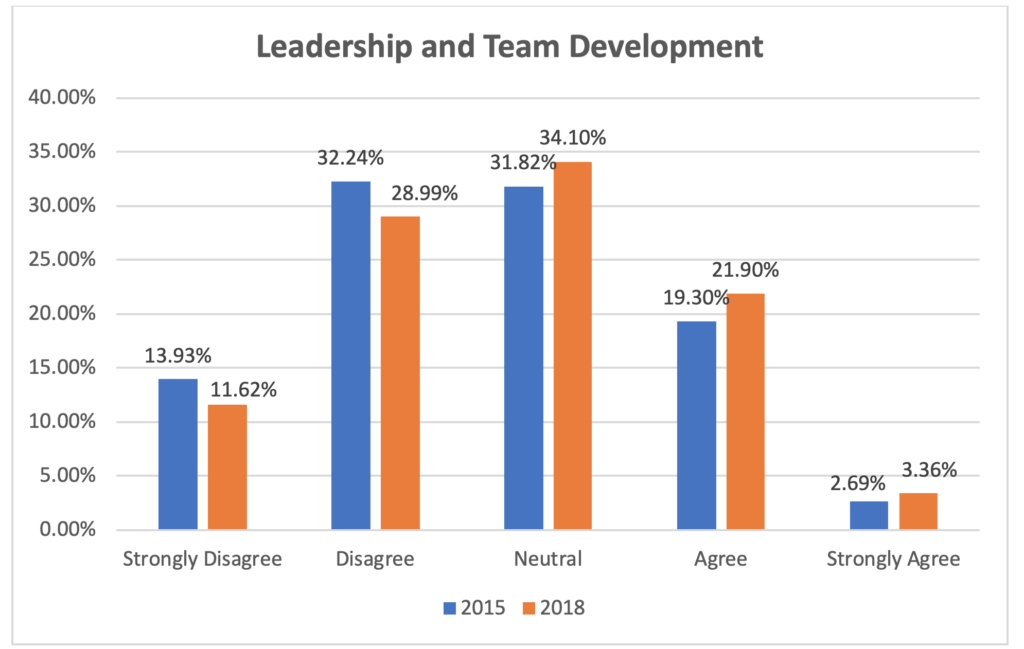

Notwithstanding the improvements, over 40 per cent of the respondents in both questions disagree with these statements. This should be a focus for most agencies involved in public service renewal. We also introduced questions about workplace perception. Here we have excellent news: 72 per cent of respondents trust the team they work within non-routine tasks, and 60 per cent

Recently, all public services made ‘disruption’ and ‘change’ their bywords. Hence, the 2018 survey asks new professionals if they agree with statements highlighting their organization’s ability to manage disruption. Results were positive, but barely so. On a weighted scale of 5.00, respondents scored their leadership’s capacity to encourage disruption 2.91; their organization’s capacity to recognize and take advantage of disruptive forces such as technology and demographic shifts received 2.92, and 2.94 was the score when we asked if their organization adapts well to change and disruption. However, asked about how well the organization did in using data to support decision making and improve service delivery, we saw a score of 3.37. A 3.27 was also scored for the organization’s attitude towards learning from obstacles, setbacks and challenging situations.

Our quick excursus barely scratches the surface of our data, but the image of new professionals in public service is one of great awareness of the upcoming challenges, strong commitment to public service values, and a desire to work in the public administration. However, we also see a certain level of frustration with the future outlook of the public service and their own career path emerging from the data. If we were to come up with a tagline to describe their attitude, we would choose Engaged but Hindered. New professionals want to make a difference, and they have chosen public service to do so; however, they feel constrained in some critical areas of their professional development.

This provides Canadian public administration with great opportunities to grow and further engage this group, but it also opens the doors to cross-sector and cross-institutional competition for their skills.