For policymakers around the world, Canada frequently leads the way on issues such as gender equality, migration or labour laws.

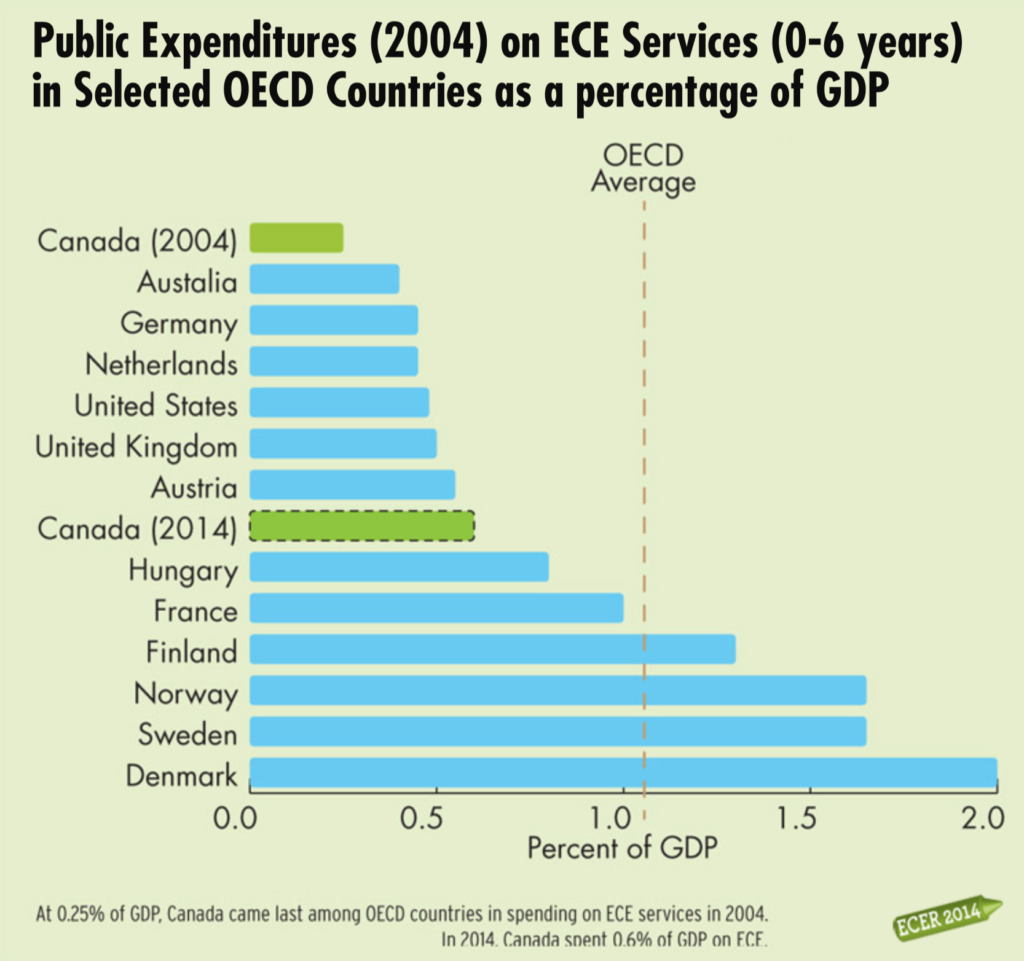

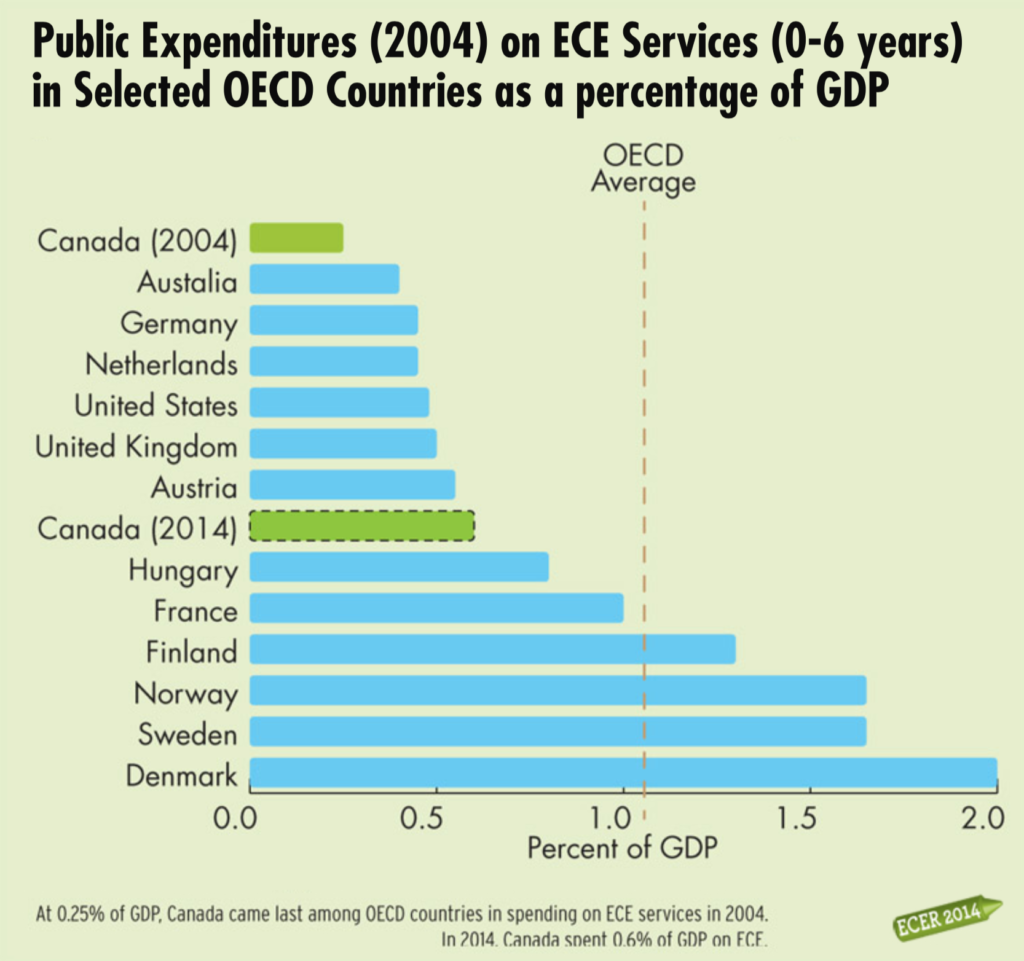

In early childhood education though the country has less cause for celebration. An OECD study published in 2006 exposed Canada’s status as a “policy laggard”, ranked last of 14 countries in terms of expenditure on early childhood education and care (ECEC). Two years later, UNICEF research placed Canada last among 25 OECD countries in its ECEC league tables.

“What really spurred the development of early childhood policy in Canada was the OECD country profile,” said Kerry McCuaig, a Fellow in Early Childhood Policy at the University of Toronto. “It had been entirely an afterthought in terms of public policy.”

Along with her colleagues at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), McCuaig has recently released the Early Childhood Education Report 2017, providing an update on what’s been achieved since.

Encouragingly, the report finds that more than half of Canadian pre-schoolers now attend an early education program before starting school, up from around 20 per cent in 2008. Meanwhile, provinces and territories have been increasing spending on early childhood since a national framework was introduced in 2006: from C$2.5b ($1.98b) in 2004 to C$10.9b ($8.6b) a decade later.

The potential of schools

The report highlighted the increasing importance of schools in providing education for children below school age in Canada: 40 per cent of four-year-olds attend school for early education.

“The evidence shows that if you want a universal system, if you want every kid to have an equal opportunity for an early education, it has to be public,” said McCuaig. “What is capturing policy-makers’ attention is that this is a child development program that every child benefits from.”

The principle is a very simple one: instead of spending money to make childcare programs universal, schools – which start at five or six years old depending on the province – “grow down” to start at a younger age. “Canada has a very robust public education system, it’s highly-regarded: 95 per cent of parents send their children to it,” said McCuaig. “Public education has the capacity to roll out fast.”

This is already being implemented successfully in provinces including Quebec, Ontario and the Northwest Territories. Quebec, for example, has been expanding full-time pre-kindergarten classes to four-year-olds in disadvantaged areas, and is looking at making this universal.

“The federal government cannot tell the provinces what to do; they can encourage them, essentially by giving them money, and they can put conditions on that money,” said McCuaig. “When that happens, it tends to focus the mind.”

Growing pains

Like any major policy change, there are challenges associated with expanding schools down to younger years.

“When jurisdictions make these kinds of decisions, there are usually huge upfront capital costs,” said McCuaig. While some schools have plenty of capacity, others are “bursting at the seams,” so creating the capacity for early childhood often needs substantial investment.

The changes could also pose danger for the private childcare sector, which currently makes up more than half of early education. “As schools take responsibility for younger and younger children, how do they do that without completely destabilising the childcare sector? Because obviously parents still need childcare,” McCuaig said. “It’s great that children can get into school when they’re three, but what happens at two?”

Meanwhile, concerns have been raised about whether growing down schools can provide the best early education for kids. The evidence suggests that in places like Scandinavia, where school starts at seven, delaying formal education in favour of play-based childcare can have a significant positive impact on early childhood development.

However, the staff for these new preschools are early childhood educators, not school teachers, and the education is very much play-based. Interestingly, schools involved have seen early childhood programs begin to influence pedagogy in older year groups.

“We actually see provinces now that are changing their curriculum for grades one, two and three, because they’ve got these cohorts of kids who’ve come in with two or three years of preschool behind them,” said McCuaig. “They’re not prepared to sit in a row and look at a teacher – that’s not the way they roll.”

A chequered record

Despite the nation’s improvements in early learning, little has changed for First Nations Canadians. “Canada’s legacy for aboriginal children is, internationally, a disgrace,” said McCuaig. “There has not been an increase in funding to aboriginal programs since 1995.”

Accounting for 4.9 per cent of the total population, aboriginal children account for 7.7 per cent of all children aged zero to four. Yet it’s been estimated that First Nations children received around 30 per cent less in funding for their education than other kids.

“It is the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government to meet the needs of aboriginal children from birth through life, and it’s just appalling,” she said. In the past few years aboriginal education has risen to prominence in the national debate, and the Canadian government has introduced a new funding package to try to make up for years of chronic underfunding.

The new OISE report, meanwhile, highlighted the significant gap in early learning between different provinces, demonstrating how much more work Canada has to do. Using a 15-point scale based on OECD benchmarks, scores ranged from 11.5 for Prince Edward Island to Nunavut, which scored a measly five.

Statistics for Canada are frequently missing in OECD reports, because provinces need to agree to provide data. “Quebec will usually agree to participate because they’re not totally embarrassed,” said McCuaig. “Then often you’ll get Prince Edward Island or one of the smaller provinces, and then one western province. You never really in these OECD reports get a Canada-wide view.”

Catching up

OISE’s report comes out every three years, and McCuaig is confident that the situation will have further improved when their next report comes out. “We expect in 2020 to see additional improvements across the board,” she said.

A ten-year federal funding agreement of C$7b ($5.6b) has been agreed to improve access to childcare, with the first instalment in 2018. Six provinces out of the 13 have signed agreements with the federal government to secure funding, while most have committed to topping it up with their own funds.

As the evidence mounts that early childhood education can increase female labour market participation, improve child outcomes, and even reduce Canada’s income inequality, urgent action is essential to boost the country’s record. Growing down schools may turn out to be the best way to meet that need.

This piece originally appeared on Apolitical, the global network for public servants. You can find the original here.