“Former Metro banker stole $73,000.”

“Enbridge sues ex-employee.”

“Woman stole $51,000 from employer.”

“Former NASA official accused in $9.6M scam.”

You don’t have to look far to find a story reporting fraud. They are everywhere. Fraud seemingly has no boundaries; local businesses, charitable organizations, banks, public companies. The list of victims goes on and on, as does the list of perpetrators, and with an estimated $3.5 trillion in potential losses worldwide annually (per a 2012 survey by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners), government departments must sit up and take notice. Identifying the conditions that lead to fraud, and gaining a better understanding of why people do it, can provide a logical starting point to help prevent fraud from happening in our organizations and to better detect it when it does occur.

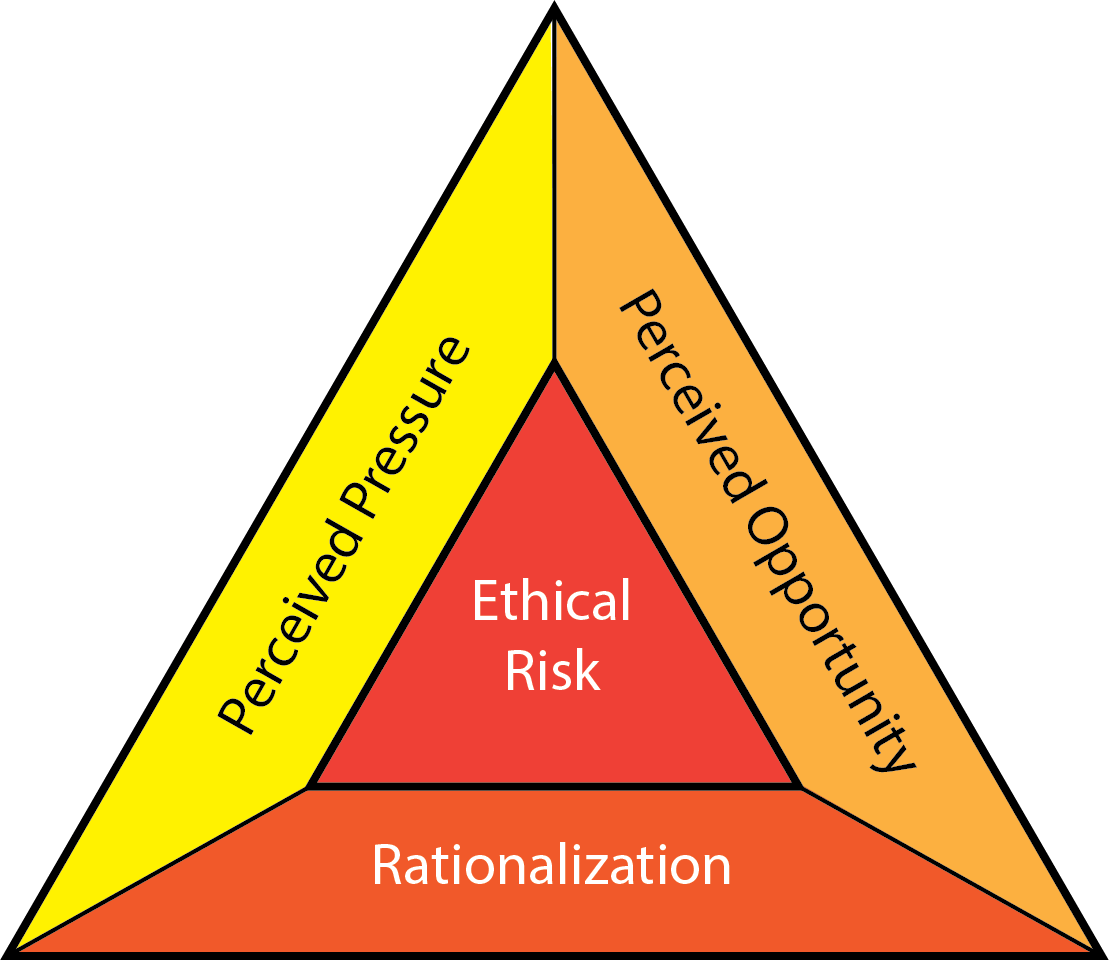

One of the most useful models to support an understanding of why fraud occurs is the fraud triangle. The fraud triangle (see figure 1) was developed from the work of criminologist/sociologist Donald Cressey. Cressey posits that fraud, a violation of trust that leads to economic or reputational gains on the part of the perpetrator, occurs in the face of a perceived pressure, a perceived opportunity, and a rationalization. While the model is the subject of ongoing research, such as the recent work by Free and Murphy (2015) which addresses why perpetrators co-offend, it provides a useful framework for understanding fraud. Each factor of the model deserves further explanation.

Perceived Pressure

In cases of perceived pressure, the perpetrator feels a pressing need in their life to prompt them to think of fraud as a reasonable alternative. Examples have included day-to-day struggles to raise a family or make mortgage payments, or less socially acceptable expenses such as gambling debts or funding an addiction. In some cases, there is undue pressure to perform, such as an expectation to bring in a certain number of new accounts or investments, and one’s tenure with the company may be in jeopardy if they do not. Faced with an inability to meet such benchmarks, the pressure to “appear” to be doing so (i.e. doing well) is perceived. In these situations, accessing an employer’s cash flow, or embellishing performance reporting, might be seen as viable options to ease the pressure.

In the case of plastic surgeon Dr. Brian Lee (as recounted by Kranacher, Riley and Wells, 2011) he concealed income from his partners because he was involved in a family competition with his brother and his father to acquire the largest pile of “things” – luxury cars, vacations and homes. Since certain plastic surgeries were not covered by insurance, and Dr. Lee required payment before surgery. So he diverted the payments from clients outside the normal billing system to further amass his own personal wealth, thus addressing his perceived need. He later confessed when a client approached the company seeking an invoice, and no record of her surgery could be found.

It is somewhat intriguing to see how this reputational factor impacts motive in fraud. Bernie Madoff, perhaps the most infamous Ponzi scheme fraudster of recent times, said his pressure was to continue to provide market-beating returns of ten to twelve percent at a time when actual returns were much lower. To do so, he falsified records to create the impression that all was more than well with his investors and their assets.

The banker from the headline above, Former Metro banker stole $73,000 said something like the doctor: part of his motivation was to convince his father he was doing well. Again, we see an incentive tied to reputation.

Of course, sometimes the needs are addiction based. We have probably all seen a news account of someone in court for fraud, their larceny prompted by either a drug or gambling addiction. In the throes of their compulsion, there is a tremendous pressure to steal from the employer or go without satisfying the powerful bodily and psychological craving. That is, indeed, perceived as a pressing need.

Perceived opportunity

When an individual has a perceived need, a perceived opportunity may come into sharper focus. There may be a chance to covertly avail themselves of some company assets or falsify documents, accessing a ready solution to meet the perceived need. In some cases, opportunities may be inadvertently noticed, presenting temptation, where in other cases, employees may be looking for such opportunities. A recent news story discussed a bizarre theft by an employee at the Royal Canadian Mint. The Mint found out the hard way that metal detectors and security cameras – what one would normally think of as excellent internal controls around precious metals – were not sufficient to stop an employee from stealing over $150,000 in gold by concealing it in a body cavity. In a Globe and Mail account of the theft, lawyer Gary Barnes offered “they had pails of gold just sitting around and people could walk by and actually just pick things out of them.” Although the employee set off the metal detector on 22 separate occasions, no one suspected his actions, until police were tipped off by a bank employee suspicious of his sizeable cheque deposits issued by gold buyers.

In another case where an Enbridge Gas employee allegedly stole $6.3 million from his employer, the scheme seems to have unfolded when the employee was promoted to supervisor, and given authority to approve invoices up to $5,000. The employee allegedly saw this as a perceived opportunity to set up a series of “shell” companies who then invoiced Enbridge for services that were never provided. These invoices were approved by the new supervisor who “owned” the companies. Opportunity was apparently knocking.

The opportunity side of the triangle is where auditors, management and accountants have the greatest influence. If controls are strong, opportunity can be removed or minimized.

Rationalization

The third side of the triangle is rationalization. Human beings are amazing creatures. Very few of us want to look in the mirror in the morning and say “I am a fraudster and a thief.” We prefer to say “basically, I’m a pretty decent person.” The notion of cognitive dissonance suggests we need a strategy to deal with the conflict between the behaviour (fraud) and the self-image (I’m a decent, hard-working person). Enter rationalization. As Donald Cressey stated, fraudsters must have “verbalizations which enable them to adjust their conceptions of themselves as trusted persons with their conceptions of themselves as users of the entrusted funds or property.”1 It is here that rationalizations such as “they won’t miss it”, “they owe this to me after all I’ve done”, or “it is just a loan – I’ll pay it back” enable the fraudulent act to be seen as acceptable in their eyes.

Looking at the story “Woman stole $51,000 from Employer”, we see a fascinating picture of rationalization at play. The Crown prosecutor noted the perpetrator said “her boss was hard to work for and he took advantage of her.” In other words, the unreasonable boss deserved to be defrauded. Bernie Madoff famously said that his investors were greedy, almost as if to say “they had it coming.” Another famous rationalization is convincing yourself, “it’s only a loan.” When a credit union employee was caught after having misappropriated thousands of dollars, she showed the authorities a careful record of her thefts. Each theft, she claimed, was actually a “loan” she had taken from the company coffers and each withdrawal was well documented. She was only waiting for the day when she could pay that “loan” back (which became increasingly unlikely as the balance mounted).

This aspect of rationalization reminds us that no matter how strong the controls, deeply motivated human beings facing a perceived need and seeing an opportunity, will sometimes cross the line into fraud. As the headlines indicate, fraud is not a respecter of persons – people within the spectrum from volunteers and minimum wage employees to multi-millionaire executives fall prey. No organization is exempt.

A better understanding of the fraud triangle can guide organizations to examine their practices to ensure there is not undue pressure to reach unrealistic benchmarks, to be more aware of employees who may be struggling financially or who seem to be making surprising financial moves (such as purchasing homes and cars that would normally be outside of their expected price range), and to more closely examine the realm of “opportunity” at all levels of a business, even when they would prefer to extend trust to their employees. The fraud triangle (although not without limitations) has endured since the 1950s, and is an important tool we can use to sharpen the focus on business practices that will benefit public sector organizations.

References

- Free, C. and P. Murphy (2015). “The ties that bind: The decision to co-offend in fraud.” Contemporary Accounting Research 32(1): 18-54.

2. Kranacher, M. J., et al. (2011). Forensic Accounting and Fraud Examination Hoboken, Jon Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Brent White is Associate Professor in the Department of Commerce at Mount Allison University.