When the Liberals announce their first ever budget on March 22 it’s going to be far larger than party promised when they campaigning to be elected.

However, while the new government has been slammed by the Conservatives and the NDP for this, some Canadian economists are saying the Liberals actually still has ample room to run a fatter deficit and that it should – with caution, though.

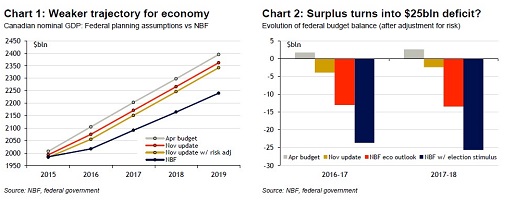

You could say Finance Minister Bill Morneau was managing expectations when he announced on Monday that Canada’s deficit will be at least $2.3 billion in the current fiscal year, $18.4 billion for 2016-2017 and $15.5 billion for the fiscal year 2017-2018.

That’s way above the Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s pledge during last year’s campaign period that he would keep the deficit to $10 billion over the next three years.

Despite these numbers, Ottawa can still afford to push the deficit a bit higher according to economists.

“When it comes right down to it, running deficits of $30-35 billion (something like 1 ½ per cent of GDP) for a few years isn’t going to erode Ottawa’s long-term fiscal sustainability,” wrote Warren Lovely managing director, head of public sector research and study at National Bank Financial in his report Anatomy of Ottawa’s Fiscal Transformation.

“Yes deficits of that magnitude in an environment of slower nominal growth might technically add a couple of percentage point to the government’s debt burden,” he said. “But given past success in wrestling the federal debt-to-GDP ratio down to size (and given rock-bottom interest rates fundamentally bolster debt affordability now and into the future) Canada needs to ask itself: do we need the federal debt burden to keep falling forever and even until the end of time? Probably not.”

If the federal government is going to be in debts it might as well be now because debt interest rates are at their lowest.

“Whether you’re a finance minister, corporate treasurer or heavily indebted household, low rates are the gift that keeps on giving,” wrote Lovely. “But you want to be careful what you wish for. As a general rule the weaker growth that attends lower interest rates is a net losing proposition for senior levels of government (i.e. lost revenue trumps interest rates savings).”

Other economists agree.

“Ottawa can clearly afford a moderate fiscal boost without doing lasting damage to the long-term debt outlook,” the Globe and Mail quoted a report by BMO Nesbitt Burns chief economist Douglas Porter and senior economist Robert Kavcic on Morneau’s update. “…The federal debt-to-GDP ratio has dipped in each of the past two years and remains relatively low at 31 per cent.”

If the Liberals should run a larger deficit, where should they spend the money on?

“As argued by many prominent economists, including former Bank of Canada Governor David Dodge, there is a strong case for deficit financing of productive public investments at a time of economic stagnation and very low interest rates,” according to the Broadbent Institute. “The government should make major investments in physical and environmental infrastructure such as public transit, social housing, and basic transportation infrastructure which will give a badly-needed, short-term boost to growth and job creation, and help raise business investment and productivity.”

An independent study by the Centre for Spatial Economics, which was commissioned by the Broadbent Institute models the economic and fiscal benefits of a plan to invest $10 billion per year for five years in basic municipal infrastructure.

Over the short-term of the building program from 2015 to 2019, GDP would be boosted by $1.43 per dollar spent. This finding is especially relevant today given very slow growth. There would be an additional 42,150 construction jobs per year, up 4.5 per cent compared to the base case, according to the study.

The study shows that business investment after 2020 would increase by $3.1 to $4.7 billion per year, or by 0.7 per cent to 1.1 per cent compared to the base case. Labour productivity growth would increase significantly, by 0.3 per cent to 0.5 per cent per year.

The benefits to Canadians of the initial investment program would be $2.46 to $3.83 per dollar spent, and GDP would increase by between $7.6 billion and $13.9 billion, according to the study.