Introduction

In a recent Opinion article in the Ottawa Citizen, Kevin Lynch and Jim Mitchell stated “A high performing public service is exactly what taxpayers deserve and the country needs…What is needed is…a common- sense approach to fixing how government operates. Here are six key problem areas, solutions to which would yield a more engaged public service and improve service to Canadians:

- …government has become too complex to manage

- …the public service is too large to operate effectively

- …oversight is too diffuse to be effective

- …accountability is too opaque

- …scant attention is paid to measuring or managing public sector productivity

- …a hesitant management culture” 1

In many cases, the solutions which the article refers to already exist in government, but are so lost in the layers of policies, directives, red tape and diffuse oversight that they do not achieve the intended results.

This is the first in a series of articles intended to describe these solutions and the changes required by the federal government to adopt them in a way which will achieve the intended results.

One of the problems is described in the article as follows – “Another productivity destroyer is long lists of policy priorities set out in mandate letters, with public servants expected to deliver on all of them. Yet the sheer number and lack of prioritization means lots of activity but few priorities actually delivered.” 1 The issue of government undertaking too many initiatives and doing them all poorly, rather than focusing on a smaller number of priorities and doing them well can be addressed by applying the discipline of (Project/Program) Portfolio Management (abbreviated PfM or PPfM) which is discussed in more detail below.

Portfolio Management (also known as Project/Program Portfolio Management)

“Portfolio management evaluates and prioritises programmes within resource and funding constraints, based on their alignment with strategic objectives, business worth (both financial and non-financial), and risk (both delivery risk and benefits risk), and moves selected programmes into the active portfolio for execution.” 2

Here is how the Project Management Institute describes PPfM:

“The Business Problem

Nearly all organizations have more project work to do than people and money to do the work. Often the management team has difficulty saying ‘no’. Instead, they try to do everything by cramming more work onto the calendars of already overworked project teams or by cutting corners during the project.

Despite a heavy investment of people and money in projects, the organization still gets poor results because people are working on the wrong projects or on too many projects. Trying to do too much causes all projects to suffer from delays, cost overruns, or poor quality.

The Solution

Effective project organizations focus their limited resources on the best projects, declining to do projects that are good but not good enough. PPfM enables them to make and implement these tough project selection decisions. 3

Note that this echoes the “productivity destroyer” described in the Lynch-Mitchell article. We will now discuss how the government has implemented PPfM, which they refer to as Investment Portfolio Management, the problems with that implementation, and how the process can be improved.

Investment Portfolio Management, the OPMCA, and the PCRA

One of the elements supporting the Government’s project management policy/directive is the Organizational Project Management Capacity Assessment (OPMCA) Tool. The assessment consists of 92 questions covering 13 of what are called knowledge areas with a maximum possible score of 460. Based on their OPMCA score, departments fall into a Capacity Class rated from 0 to 4. The first knowledge area in the assessment is Investment Portfolio Management which “refers to the selection and support of projects or investment program investments. These investments in projects and investment programs are guided by the organization’s strategic plan and available resources”.4 In order to score well in this knowledge area the organization must (among many other things):

- Select, prioritize, and resource its portfolio of planned projects according to their contribution to the organization’s strategic objectives as outlined in the Program Alignment Architecture (PAA)

- Consider human and financial resource capacity and capability in determining the timing and amount of project work it undertakes

- Employ a process by which redundant projects are eliminated

A second element supporting the Government’s project management policy/directive is the Project Complexity and Risk Assessment (PCRA) Tool. This risk assessment consists of 64 questions covering 7 risk areas with a maximum possible score of 320. The Treasury Board Policy on the Management of Projects requires deputy heads to ensure that each planned or proposed project which is subject to the Policy is accurately assessed to determine its level of risk and complexity for the purposes of project approval and expenditure authority.

How are the OPMCA and the PCRA related, and why are they important? The dollar value threshold for which a department is required to prepare a PCRA for individual projects depends on their Capacity Class. Departments with a low Capacity Class must submit a PCRA for any project over $2.5 million, while those with the highest Capacity Class are exempt from the PCRA for projects under $25 million.

On the surface, this all seems reasonable. Both the OPMCA and PCRA are based on widely accepted project and investment management frameworks. But as is too often the case, these frameworks have been implemented in a way which is so bureaucratic, complex, and time / effort intensive that they are not nearly as effective or efficient as they should be. Specifically:

- 92 questions for the OPMCA and 64 for the PCRA is far too many. The questions themselves take at least 30-50 screens to scroll through if not more. I have seen an OPMCA submission from one Department take over 3 months to complete and involve 10 or more senior managers at the Director and DG level. Fortunately, the OPMCA is only prepared every three years, the downside being that for most staff, their first time participating in the process will be the only time they participate.

The PCRA uses a computer system supported by TBS called Callipers. Callipers is old and in need of being modernized, particularly as regards its user interface, rudimentary workflow, and its inability to store all of the supporting documents that need to be submitted. Accordingly, many departments use an Excel spreadsheet for working drafts of the PCRA and only enter information into Callipers when it is finalized. The PCRA process involves three levels of users – authors, reviewers and approvers, and can involve multiple iterations back and forth between these levels both within a Department and between the Department and TBS.

- Both assessments can be gamed to some extent. For example, the Department has input as to which projects are included in the OPMCA, and it is amazing how many projects fall just under the approval thresholds which the Department has been granted. Also, many of the questions in both assessments are qualitative or subjective in nature. For example, consider question 3.1.2 of the OPMCA – “To what extent is the portfolio of planned projects selected, prioritized, and resourced according to its contribution to the organization’s strategic objectives as outlined in the Program Alignment Architecture (PAA) in support of the Management Resources and Results Structure (MRRS) Policy?” Alignment is measured qualitatively, and it is not difficult to spin a narrative which supports the assertion that a given project is aligned with a particular strategic objective, especially if that objective itself is also qualitative.

Having discussed the government approach to PPfM above, we will now describe an approach which is commonly used in the private sector and then conclude with suggestions on how the government process can be streamlined and made more effective.

Investment/Project Portfolio Management Essentials

The PPfM process consists of two steps and is intended to be applied organization-wide. Step 1 is to prepare a list of all candidate projects being considered for funding approval. Using a standardized, well-structured scoring instrument and a rigorous, repeatable process, each project is scored on a scale of 1 to 10 on two dimensions – value and risk. The result is that all projects are plotted on a grid as illustrated at right.5 Note that in the public sector, value is a combination of alignment with mission goals and quantifiable benefits which should be significantly based on the DRF/PIP. The risk score can be derived from elements of the PCRA.

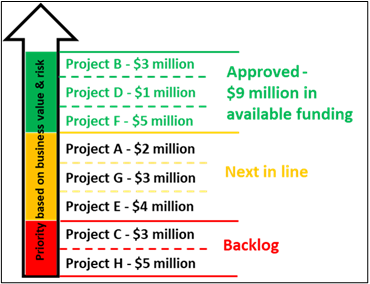

Once all projects have been situated on this value versus risk grid, Step 2 is to stack the projects from lowest priority to highest (based on business value and risk). A line is then drawn based on the organization’s budget and resource capacity – see the figure at right. Those which fall above the line (in green) are funded and moved into the active project portfolio, those just below the line (in yellow) are managed as the pipeline of “next in line” should additional resources become available, and those well below the line (in red) are shelved and reconsidered when the portfolio planning exercise is next repeated.

The two-step process described above must be tightly integrated into the Departmental budgeting and project gating processes. Most departments have some flavor of project approval board. Typically, the project manager and project sponsor present to the board which then has the authority to approve or reject the project. The PPfM process requires that all new projects being considered for approval be assessed against the same risk and value criteria so that they can be compared against each other and prioritized.

Improving Investment/Project Portfolio Management in Government

Comparing the Investment Portfolio Management process driven by the OPMCA and PCRA which the government uses to the PPfM essentials as described above, how can the government processes be streamlined and made more effective?

- Complexity is in fact a significant element of risk, so the PCRA can be modified to produce a single, standardized Project Risk Assessment score. Elements of the DRF and PIP can be adapted to allow all projects to be scored on a standardized scale, thus becoming Project Value Assessment. The risk and value scores can then be used to plot all projects on a single grid as depicted above so they can be compared to each other and prioritized.

All projects should be assessed for both risk and value – that is a universally accepted project management best practice. But the tools and processes used should be simple and streamlined so that completing them will not be seen as a bureaucratic hurdle to be avoided whenever possible, or that not doing them for all projects is seen as a reward for departments seen as more competent in managing projects. The risk and value assessment tools and processes should be redesigned to be used initially in a workshop lasting at most two days attended by at most 10 empowered decision makers – once and done and consensus-based, not endless revisions and iterations. The workshop must be held at the point in the budget process where the results can be used to determine which projects to fund and which not to. The process can be repeated in the event of major budget changes or if government and/or departmental priorities change significantly during a fiscal year. These tools and processes can be designed in two flavors – light for smaller, less complex projects, and full-fledged for all others. Once the value and risk assessment processes are streamlined, the OPMCA process can then be eliminated.

TBS should participate in the workshop(s) referred to above, especially for the larger, more complex projects. Eliminate the bouncing back and forth between the department and TBS – once and done and consensus-based. But the primary accountability for a department staying within its budget and delivering projects successfully must remain within the department.

Also, the collective mindset towards accountability in government needs to change. The Lynch-Mitchell article states that “accountability is too opaque”. Two mind sets need to change:

- First, the mentality that “we followed the process so we can’t be held accountable if things go awry”.

- Second, the mentality that “if we get enough people involved in these decisions and get TBS approval, it will be impossible to determine who to hold accountable if things go awry”

The group of decision makers participating in the PPfM workshop must be held accountable for their prioritization decisions, and the project manager, the business owner and the IT project lead, all of whom are appointed by the department, must be held accountable for delivering projects on time and on budget and for ensuring that the benefits used to justify the project are actually achieved. The whole concept of accountability in the federal government must also be re-visited, but that is a complex issue deserving of a full separate discussion. A Forbes article briefly summarizes the issue with accountability: “Accountability often gets a bad rap, especially in the workplace. When people are told they are accountable, a failure-phobic mindset can set in. Employees may believe that if the goals aren’t reached, they’ll be called out in front of colleagues or become a scapegoat. To shield themselves from the misperception of accountability, employees play the blame game, pointing fingers and ignoring the problem.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In fact, it can’t be that way if a company truly wants to achieve its goals. Leaders must de-weaponize accountability and turn it into an opportunity for success. By doing so, they can create a culture that nurtures positive accountability, giving employees both the desire and the confidence to step up. As employees take ownership of their actions and responsibility for outcomes, greater productivity and success result. In the end, companies thrive across every metric…” 6

- The OPMCA illustrates how confusing TBS policies and directives can be. No doubt these are meant to be understandable and easily accessible to managers in Government, but in practice they are anything but. Here is an example. Question 3.1.2 of the OPMCA referred to above comes from Version 1.4 of the OPMCA which is apparently the most recent version. But perhaps it is not the most recent version, since the question references both the MRRS and the PAA, and yet the policy on the MRRS on the TBS website appears with the following headline:

Note that although the policy on MRRS was rescinded in 2016 (presumably along with the PAA), the TBS website does not state what these were replaced by, and the OPMS tool still references both these rescinded items. Apparently, the MRRS and PAA have been superseded by the Policy on Results (PoR) and the Departmental Results Framework / Program Inventory / Performance Information Profile (DRF/PRI/PIP). Hopefully, this alphabet soup does not confuse public sector managers as much as it confuses me.

Worse yet, a search of the Canada.ca website using the terms DRF, PRI or PIP yields hundreds of search results, not one of which provides specific guidance on the contents or format of these deliverables. Samples of the DRF and PIP developed by departments for specific projects are provided, but neither the Policy nor the Directive on Results include detailed guidance on the DRF or PIP against which to assess the quality of these samples. Guidance and samples for the format and contents of all documents specified in TBS Directives and Policies should be provided and kept up-to-date. In addition, all Treasury Board Policies should include a version history and, if rescinded, a clear reference to what replaces them and why. Finally, TBS needs to be more aware of the impact which the policies and directives they issue have on departments. First, complex policies and directives that require multiple iterations and significant time and resource commitments by middle and upper management without adding demonstrable value to the day-to-day responsibilities of these managers will be actively avoided. Second, policies and directives that are not actively enforced perpetuate the notion that there are no real consequences to non-compliance – just ignore TBS and eventually they will go away.

Call to Action

Better to focus on a small number of initiatives and do them well than to undertake a large number of initiatives that are under-resourced, and then fail at many of them. My call to action is to the middle managers in the federal government. If senior management will not make the difficult decisions to prioritize and focus, stand up and demand that they do so. Also, apply this same approach to your personal work plan and that of the team you manage. If you are asked to participate in something new/unapproved which will pull away resources from your agreed-upon priorities, just say no and encourage your team to do the same. Just because someone asks you to work on something does not require you to agree – focus ruthlessly on your priorities and complete them as quickly as possible with the highest possible quality. Make it clear that if you take on something new, you either require net new resources or one of your approved priorities will need to be dropped. It will make your job more rewarding and less frustrating, and will deliver far better results.

References:

- Six ways to help the public service, Kevin Lynch and Jim Mitchell, Ottawa Citizen, December 14, 2023

- https://csbweb01.uncw.edu/people/ivancevichd/classes/MSA%20516/Extra%20Readings%20on%20Topics/IS%20Governance/IT%20Value/Val%20IT.pdf

- https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/project-portfolio-management-limited-resources-6948

- https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/information-technology-project-management/project-management/organizational-project-management-capacity-assessment-tool.html

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/puar.13633?af=R

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2023/10/18/5-steps-to-inspire-positive-accountability-in-the-workplace/?sh=57490aeaffce