There was a time when people who ran meetings were chairmen, whether male or female. Local officials were aldermen. Women were either Miss or Mrs.

Those terms seem quaint now (or to young people, perhaps other-worldly) but they turned out to be surprisingly fiercely held and the passage past them emotional and divisive. The transformation is not over, however. Our understanding of gender and the language related to it continues to be challenged. We now live in a world of cisgender, transgender, and LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender), with emails, suddenly stating the preferred pronouns or honorifics for the sender.

For government executives, these are not small issues. They relate to workplace colleagues and the public that is served. Yet sometimes it can seem baffling.

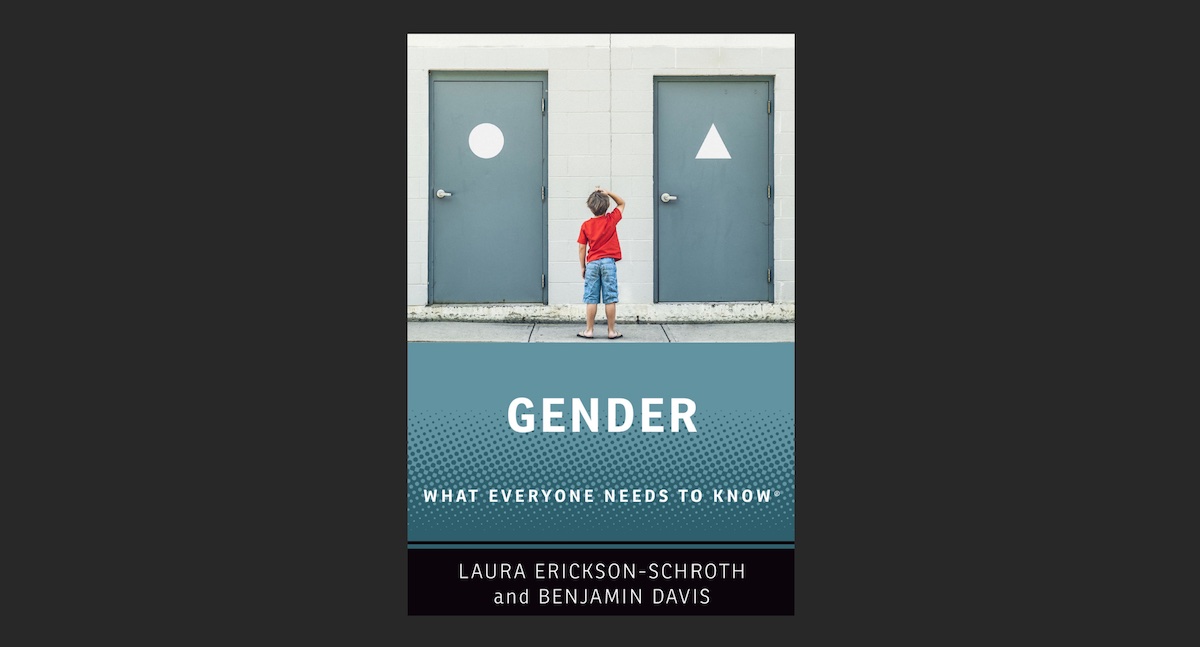

Gender

By Laura Erickson-Schroth and Benjamin Davis

Oxford University Press, 194 pages, $9.99 (Kindle)

A good place for improving understanding is the guidebook Gender, by Laura Erickson-Schroth, a New York City psychiatrist who specializes in LGBT health, and Benjamin Davis, a psychotherapist and art therapist in that same city. It’s part of the What Everyone Needs to Know seriesof balanced and authoritative primers on complex current event issues and countries, written in question and answer format, like an encyclopedia.

For example, quite basic, but not necessarily something most people can answer: How is gender different from sex? Although we use the terms interchangeably, sex refers to physical characteristics and is usually assigned at birth as either male or female, depending on the appearance of the genitals. Gender refers to the social aspects of identity. Some people are intersex, their body not fully matching our expectations of male and female. They may be identified at birth but many are not.

Gender identity is our self-conception of who we are – our innermost sense of being a man, woman, or something else. Most commonly, gender identity is consistent with our sex assigned at birth. “But what makes someone a man or a woman? What is gender identity really? If a woman undergoes a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus), most would agree that this does not mean she is no longer a woman. If a man needs one or both testicles removed, he may grapple with what this means for his masculinity, but he remains a man,” they note.

So something beyond body parts connects us to our womanhood or manhood. That something else is gender identity. It’s how our brains think of ourselves as gendered beings.

Gender expression is a term used to describe a person’s outward appearance. Clothing, jewelry, and hair length are commonly gendered as well as certain activities, interests, and mannerisms. Acting tough is equated with masculinity; a nurturing and general manner considered feminine. This can change over a lifetime – young people, the authors note, will often present in hypermasculine or hyperfeminine ways but as they come to understand themselves better become less stereotypical. Gender expression is about actions, not necessarily corresponding to internal identification.

This builds into gender roles, the unspoken duties that are assigned to a person based on their sex or gender. It’s what a community expects women and men to think, feel and do. Gender roles vary throughout the globe and over time. “As one strays from culturally accepted gender roles, a common experience of skepticism or devaluing occurs. Men who appear too feminine become comical to the public eye and women who possess qualities aligned with masculinity can be ridiculed for being bitchy or bossy, overemotional, hysterical, and frigid,” they write. Often moving away from the expected gender role leads to questions about the person’s sexuality. A boy seen to be “acting like a girl” will be called a faggot.

The term gender binary has recently drawn attention. It contradicts something we have long taken for granted: An individual must be either male or female. This instinct can arise even before birth – “baby girl” or baby boy” will often be the reference to the embryo. The desire to label in this fashion focuses us on characteristics exclusive to one gender or the other, rather than paying attention to traits that many people across different genders share.

“Inherent in the gender binary is power. In most modern cultures, men hold more power than women, and those who identify outside the binary are often highly criticized, objectified, and targeted for violence. Gender fluidity in a world that is largely invested in a binary system of gender can be threatening and confusing because of existing power dynamics,” they say.

Despite this, we are hearing of and encountering people who proudly proclaim they are non-binary or genderqueer. They may see themselves as androgynous or gender-neutral, or may simply be opposing the strict boundaries of binary gendering. This can be threatening to some but the authors argue that as non-binary identities become more accepted everyone can benefit from a more expansive definition of gender.

“Nearly everyone can recall a time when their behaviour was not completely in line with gendered expectations. It may have been subtle. For a man, voicing emotions or crying could feel gender nonconforming. For a woman, negotiating a salary might feel far from the way she was taught to behave in the workplace. Likely we were not socialized or taught that these behaviours were accessible to us while growing up,” they write.

The term transgender refers to someone who identifies with a gender that is outside the expectations associated with the sex they were assigned at birth. Men who were born with vulva and ovaries will be referred to as transgender men or trans men. Women who were born with a penis and ovaries are called transgender women or trans women. This needs to be separated from sexuality or sexual orientation – whether they identify as gay, lesbian or queer. “Transgender is not an ‘extreme version’ of being gay. In fact, many transgender people partner with a different gender and identify as heterosexual,” they note.

Intersex people are those whose sexual or reproductive organs develop differently from the typical male or female pattern. They used to be called hermaphrodites but that is now considered offensive. Some intersex people consider themselves part of the LGBTQ spectrum but some don’t, and so you may see the term LGBTQIA, which includes intersex and asexual individuals.

While this seems a modern phenomenon the authors trace these notions back through time. Plato’s Symposium discusses a creation myth involving three original sexes: Female, male and androgynous. North American indigenous tribes cover a range of non-binary identities with the term Two Spirit. In Mexico’s Oaxaca region, the Zapotec communities recognize “muxes,” people who were born as male identifying as female or existing totally outside the male-female binary. A 1974 study estimated that six per cent of the males in that community were muxe.

The authors say that that the languages we speak have the potential to shape the way we think about gender, notably sexist language. For many years the default pronoun in English was he when gender was unknown. Suggestions to change that drew howls of protest, as did the notion that we should use neutral terms like spokesperson and firefighter instead of more gendered language. Ms., which we now use as an equivalent to Mr., when not signifying marital status, was coined in the 1960s but actually dates back to the 17th Century. Using “they” to describe an individual when gender is unknown also dates back to the past, including Chaucer and Shakespeare. Some transgender and non-binary people have been choosing gender-neutral terms and those may come into mainstream use, Mx. being the most popular. Ze has been proposed to replace her or him and hir to replace him or her. But the most common gender pronoun is they/them.

Gender may not seem like a leadership book. But government executives must adapt to the communities they serve in respectful ways. With something as complex, confusing, and explosive as gender, this book offers sound, level-headed explanations, with admirable research and historical depth. Also valuable are Gender: Your Guide by Queen’s University education professor Lee Airton, which has a similar explanatory element combined with some details on her own transition from female to a non-binary transgender person, and Transitioning in the Workplace: A Guidebook, by Dana Pizzuti, who left work one day as the male senior vice-president and returned after medical treatment as the female vice-president.