As governments around the world move towards the digital transformation of service delivery, ensuring social inclusion is a pressing imperative. Like other countries, Canada has advanced the provision of information and services to citizens in an increasingly electronic format. At Employment and Social Development Canada, one of the largest federal departments serving Canadians, many services and information are delivered by Service Canada – the brand with which most Canadians are familiar.

In the context of rapid technological change, digital services are seen as being in sync with citizens’ expectations of getting information and doing business electronically with ease. The movement towards having all services available electronically is anticipated to improve access for citizens, lower program delivery costs, and increase ease of obtaining information and conducting transactions electronically. While these assumptions have been borne out to varying degrees across programs, the full potential of digital services has yet to be realized.

The well-established evaluation function at Employment and Social Development represents the crossroads between program performance, social science methods, and policy advancement. By assessing “what works,” the evaluation function is well-placed to contribute to the evidence base needed to support an effective “transmission grid” along the policy-program-delivery continuum.

The implementation of even the best-designed policies and programs can be difficult and result in unintended outcomes. Evaluation findings across programs show that implementation and on-going delivery can and does impact program success; moreover, certain sub-populations are consistently found to face challenges.

We focus here on findings that emerged from qualitative data (data collection methods included in-depth interviews with Service Canada staff, and focus groups with organizations serving specific sub-populations of seniors) gathered between 2008 and 2015 as part of evaluations of three ESDC programs targeting Canada’s senior population:

- Summative Evaluation of the Canada Pension Plan Retirement and Survivor Benefits (forthcoming)

- Evaluation of the Guaranteed Income Supplement Take-up Measures and Outreach (2010): http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/rhdcc-hrsdc/HS28-174-2010-eng.pdf

- Evaluation of the New Horizons Program for Seniors (2015) : https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/reports/evaluations/2015-new-horizons-seniors.html

While seniors are not a homogeneous group, these evaluations identified similar sub-populations of seniors who may experience common barriers in accessing services and, in some instances, benefits to which they are entitled.

Across these three evaluations, sub-populations of seniors identified as vulnerable included: older seniors, immigrant seniors, Indigenous seniors, and seniors in rural/remote geographic areas.

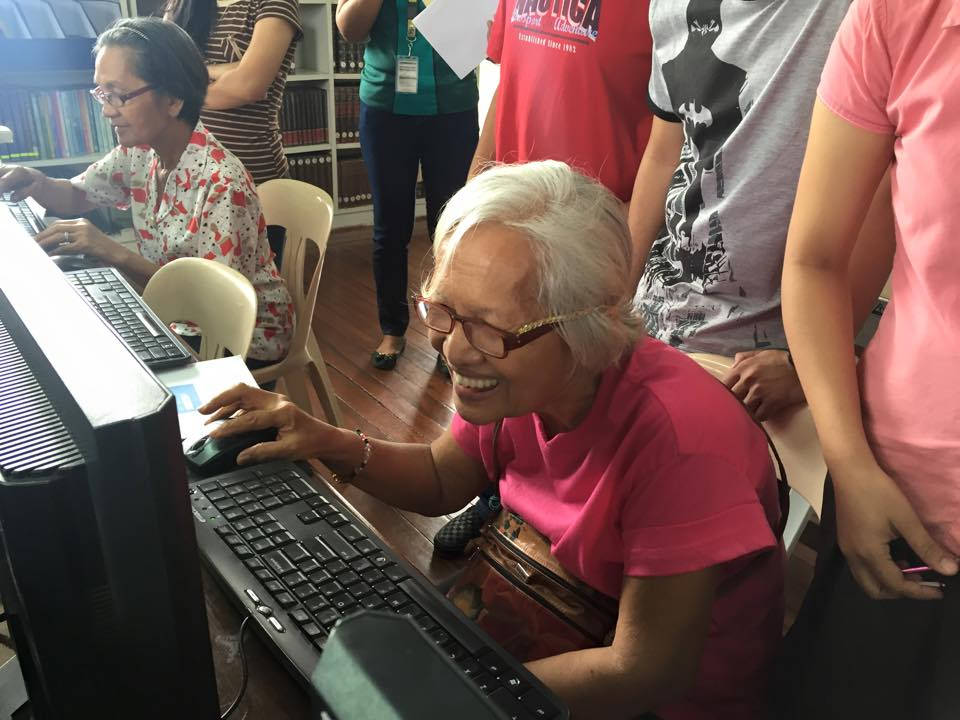

The common barriers they found included: lack of comfort using computers; lack of computer literacy; limited or no access to computer, printer, or Internet; need for assistance or one-on-one support; language or cultural barriers; literacy issues and difficulty filling in forms; mistrust or fear of government; physical and/or cognitive issues; access to banking including lack of a bank account and lack of access to a bank and/or automated teller machines (ATM). Any of the groups of seniors may experience one or more of these barriers.

The findings from one evaluation indicated that seniors accessed Service Canada via all three of its service delivery channels (i.e., in-person, telephone, and the Internet). It was also reported that seniors also gained information about pensions via word-of-mouth from friends and family. Service Canada Centre interviewees also reported that their senior clients who had used the in-person service relayed that they had not accessed the Service Canada website or called 1-800-O-Canada. This resonates with findings from another evaluation which found that, while recognizing the differences that exist among seniors, as a group, they tend to depend less on the Internet and modern technologies and could be more responsive to traditional means of communicating such as print, telephone or face-to face contact.

A lack of computer literacy, lack of access to computer hardware or software, or lack of access to Internet access all pose considerable barriers to accessing information or conducting transactions digitally. While it is possible to access public computers, for example at public libraries, several of the other barriers identified above, such as poor literacy and/or poor computer literacy, lack of fluency in English or French, or physical and/or cognitive impairments, limit the use of such public computers.

For example, a number of Service Canada staff interviewed as part of the evaluation reported that although they have assisted senior clients to set up a My Service Canada Account, several of those clients have subsequently found it challenging to recall user names and passwords. It was reported that some older seniors also experience physical and/or cognitive challenges using the telephone channel, with particular examples including poor hearing, poor memory, and difficulty in understanding the list of options when calling the 1-800 number.

One evaluation discovered a particular challenge for Indigenous seniors: Legislative and regulatory factors concerning employment on and off reserve have unique implications for their contribution-based pensions. It was reported that this issue is often not well-understood, and that many of these seniors are unaware that their monthly pension cheque may actually include multiple benefits. As a result, Service Canada staff emphasized the importance of outreach and education so that current Indigenous workers have the information needed to plan for retirement.

In addition to the complexity of the pension programs, service delivery elements also pose barriers to many Indigenous elders. For example, it was reported that many Indigenous people, especially elders, find it stressful dealing with government, and are concerned that they will “get in trouble” if they make a mistake on forms. At the same time, it was reported that the bureaucratic and legal language in government forms makes reading and completing the information challenging. Those living in remote areas may not be able to travel the long distance to the nearest Service Canada Centre, and for the reasons noted above, may find it difficult to use the phone line. It was reported that many Indigenous seniors in remote locations prefer the in-person services provided during scheduled outreach sessions.

Similar to some Indigenous seniors, immigrant seniors may also experience language and literacy barriers. Evaluation findings indicated that these seniors often rely on assistance from community agencies and adult children to complete application forms and understand pension programs. It was reported that seniors who have immigrated to Canada later in life, after contributing to pensions in their home countries, may be unaware of the International Social Security Agreements, and as a result, they may not be receiving pension benefits for which they would be eligible based on contributions made outside of Canada. Similar to Indigenous seniors, immigrant seniors may face multiple barriers to accessing the information they require and receiving the full benefits to which they may be entitled. As was suggested for Indigenous seniors, Service Canada key informants suggested that additional outreach and education targeting immigrant seniors groups may be an important service.

As one evaluation notes, approximately one quarter of seniors in Canada live in rural areas and small towns, so they may be more vulnerable than younger populations to barriers associated with living in rural/remote locations. According to another evaluation, these barriers include the difficulty of accessing in-person services which may be located in another town, having limited access to the Internet, and even limited access to banking facilities. Even during scheduled outreach sessions to more remote areas, it was reported that unstable Internet access has interfered with the ability to provide information and services to clients. It was also reported that in some remote locations there are no banks or ATMs, thus raising the possibility that mandatory direct deposit may pose challenges for some.

Several of the barriers identified here such as literacy issues, language and cultural barriers, limited Internet/computer access, could also impact non-senior populations. Research suggests that citizen expectations’ of service support varies depending on the nature of the interaction (e.g., seeking information versus trying to resolve a problem).

The responsibility and accountability associated with providing service to citizens varies from that of serving customers and clients. (While there may be similarities between citizen-centred service and customer satisfaction, they are not the same. For more on this distinction see Henry Mintzberg “Managing Government, Governing Management”, Harvard Business Review Reprint No. 96306.) The inherent distinction being that citizens have a right to specified services from their governments; whereas, customers and clients of private and other organizations have different relationships and related expectations.

Currently, Employment and Social Development is undertaking a significant transformative agenda rethinking its service delivery, including: design, meeting clients’ expectations, innovation, collaboration with external partners, and leveraging technology solutions. This agenda is informed by input from employees, private sector expertise, direct citizen engagement, co-design and prototype options. While these efforts may be responsive to many client needs, findings highlighted in this article suggest that the increasing use of electronic government services could have the unintended result of making it more difficult for vulnerable groups already experiencing challenges to easily and effectively access services they need and to which, as citizens, they are entitled. In that context, work has been initiated with NGOs, clients and staff to identify barriers for those using digital services, and to co-develop service delivery solutions — both digital and updated non-digital processes. Finally, results from a current evaluation of service delivery via in-person, telephone and online channels will inform further changes so that all citizens are effectively served.

Christine Minas is Director of Evaluation, Employment and Social Development Canada and Lisa Comeau is Evaluator, Employment and Social Development Canada. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Employment and Social Development Canada or of the Government of Canada.